This article first appeared in BusinessMirror on March 21, 2025.

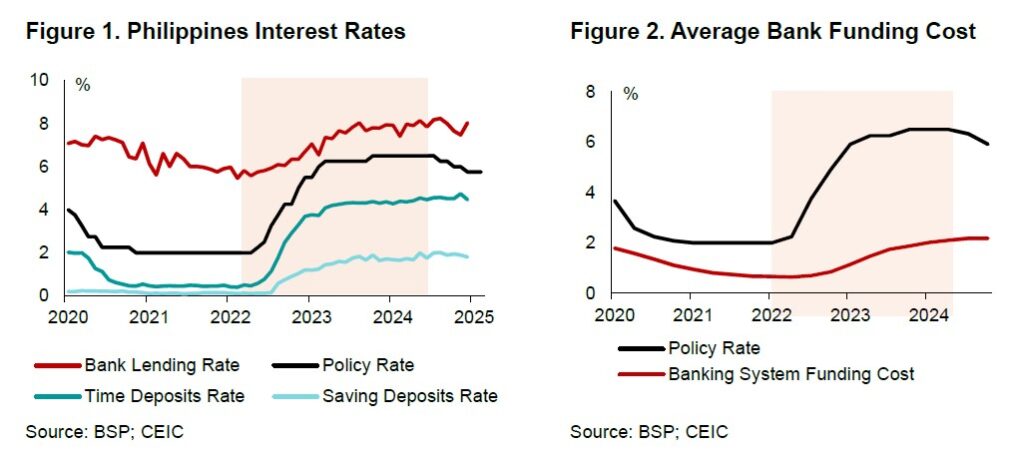

Since inflation in the Philippines started to surge in 2022, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) has raised the policy rate by as much as 450 basis points over a three-year period, with the rate peaking at 6.5 percent in the first half of 2024. However, three months after the last rate hike, the average bank lending rate has risen by only around half of the policy rate hike (Figure 1).

Although the hiking cycle has ended with the BSP cutting the policy rate in August 2024, it is worth examining why bank lending rates were so sticky in this last tightening cycle. Given that bank lending is the principal source of financing for households and firms in the Philippine economy, effective monetary policy transmission through changes in bank rates is crucial for achieving the country’s price stability targets.

Abundant low-cost deposits, slow bank funding cost adjustments

Despite a smooth pass-through from policy rate to short-term market rates, bank funding costs have remained largely unresponsive. Following the 450-basis-point rate hike, average funding cost for Philippine banks increased by less than one-third of that amount (Figure 2). With funding cost sticky, bank lending rates have also been slow to adjust.

A key reason behind this rigidity is the dominance of low-cost deposits. Close to 90 percent of the liabilities of Philippine banking system come from deposits. Of this, 75 percent are low-cost deposits, mainly demand deposits, negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts, and savings deposits. This ratio is significantly lower in peer countries like Malaysia (53 percent) and Indonesia (61 percent). As these savings and demand deposits pay lower interest rates and adjust more slowly than term deposits, they keep banks’ funding costs insulated from policy rate shifts.

One factor for the abundance of low-cost deposits in the Philippines is the lack of competition from other safe and liquid savings alternatives in the market. In addition, ample liquidity in the banking system reduces the incentive for banks to compete actively for funding by raising deposit rates or attracting more term deposits. Indeed, the Philippines’ loan-to-deposit ratio of around 70 percent is considerably lower than that of peer countries.

Uneven pass-through across loan types

In addition to the weak transmission to the average lending rate, the pass-through rate varies significantly across loan types. During the latest interest rate upcycle, while corporate loans experienced the strongest pass-through at around 64 percent, SME and household loans saw only 32 percent and 20 percent pass-through rate, respectively. Moreover, interest rates on salary and motor vehicle loans declined even as the BSP raised its policy rate.

The divergence stems largely from the significant credit risk premium embedded in SME and household lending rates. Due to deficiencies in the credit data infrastructure, banks struggle to accurately assess the risks associated with small borrowers. While both public and private credit information providers exist in the Philippines, problems with data quality, coverage, and consistency limit their usefulness. Furthermore, many Filipino households still lack formal credit histories. For these reasons, banks often impose uniformly large mark-ups on lending rates as a prudential measure. When lending rates are dominated by large credit risk premium, changes in the policy rate become muted.

Enhancing transmission in lending rates

To increase the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission to bank lending rates, the following policy approaches can be considered:

- Increase competition in the deposit market by promoting greater availability of savings alternatives, including higher-yielding term deposits and capital market investment products, such as unit trust funds. This initiative can go hand in hand with the BSP’s financial inclusion and financial literacy efforts. At the same time, the government can consider expanding tax incentives for capital market investment vehicles and introducing government-led investment funds. A regional example of these is Malaysia’s Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB). These efforts will not only expand savings alternatives but also deepen the domestic capital market.

- Improve credit data infrastructure to enable banks to better price credit risk and interest rate risk in their lending rates. In addition to borrowing records, credit data can be expanded to include non-traditional sources such as utility payments and online transactions to provide a more comprehensive picture of borrowers’ creditworthiness. A more robust credit reporting system can also improve financial inclusion, as it allows borrowers with strong credit histories to access credit at more favorable rates.

Ultimately, the weak pass-through of policy rate to bank lending rates during the 2022-2024 hiking cycle was primarily due to the insensitivity of banks’ funding costs to the policy rate and the weakness in credit data. Strengthening competition in the deposit market and improving credit data infrastructure will not only enhance the effectiveness of monetary policy in the Philippines but also advance broader financial development and inclusion.