In March, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) terminated its nearly decade-long unconventional monetary policy framework, characterized by massive asset purchases, negative interest rate, and yield curve control (YCC) policy.

Additionally, the BOJ raised its policy rate by 0.1 percent to a range of 0-0.1 percent, citing the long-awaited emergence of a virtuous cycle between wages and prices.

Indeed, Japan’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has been gaining momentum as evidenced by the “core-core” measure – excluding the volatile items of fresh food and energy – persistently remaining above 3 percent for nearly a year.

The momentum of high nominal wage growth is also expected to continue. This year’s average wage increase is likely to surpass the previous year’s 3.6 percent, reaching over 5 percent—the highest level since 1991, as indicated by the preliminary results of the annual spring wage negotiation.

Despite implementing its first rate hike in nearly two decades, the BOJ opted to maintain its accommodative policy stance, as stated in its March policy statement.

Against this backdrop, what is an appropriate level for Japan’s interest rates in the post-YCC era, particularly after the BOJ shifted to use the short-term interest rate as a primary policy tool?

Equilibrium for Japan’s rate of interest

Economists have long demonstrated a passion for developing concepts and models to identify equilibrium interest rates, which can be used to assess the ups and downs of economic data such as GDP growth and employment.

In the same vein, the concept of the “neutral rate of interest”, or r-star (r*), represents the equilibrium level of real interest rate that neither accelerates nor decelerates economic activities and inflation.

In theory, the r-star should move in alignment with the economy’s dynamism, approximately equal to the potential growth rate. However, in the short term, it can deviate from the trend growth and move along with cyclical factors such as fluctuations in capital supply and demand, as well as saving and investment.

Several studies on the Japanese economy have pointed out that there is a declining trend in its r-star, influenced by structural factors such as an aging population, increasing domestic saving, and reduced business dynamism.

However, in reality, obtaining the unobservable r-star is a complex undertaking.

Rise of r-star after a long period at zero

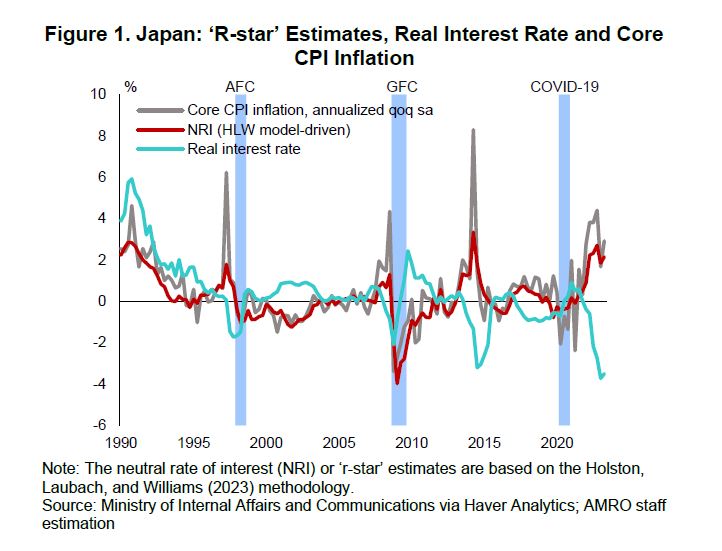

A recent study conducted by AMRO staff indicates that Japan’s r-star has significantly increased, aligning with the acceleration in core CPI inflation and the gradual recovery of the economy (Figure 1).

The study found that starting from the mid-1990s, Japan’s r-star estimates—measured in real terms—generally fluctuated around zero.

An exception is that during the global financial crisis in 2008 which was marked by a sharp decline in both real GDP growth and core CPI inflation, the r-star experienced a significant drop, too.

However, when the economy contracted sharply amid the COVID-19 shock while core CPI inflation only moderately decreased due to global supply disruptions, Japan’s r-star only declined briefly and slightly.

Since 2022, with the recovery of Japan’s economic activity and an acceleration in core CPI inflation, the r-star has risen significantly, reaching around 2 percent, albeit with a large margin of error in the estimation.

Time to further raise policy rates?

According to our analysis, there is a high positive correlation between the r-star for Japan and its CPI and economic growth. As the analysis suggests that Japan’s potential growth rate recovered gradually to about 0.5 percent in 2023, its r-star is now on the rise amid heightened inflationary pressures, indicating an increasing need for the BOJ to raise the policy rate.

Since early 2022, the BOJ’s monetary policy stance has implicitly become less accommodative, particularly with the greater flexibility in its YCC. However, as the r-star has also increased, there is room to reduce the extent of the BOJ’s monetary easing or to normalize the current negative interest rate policy more explicitly.

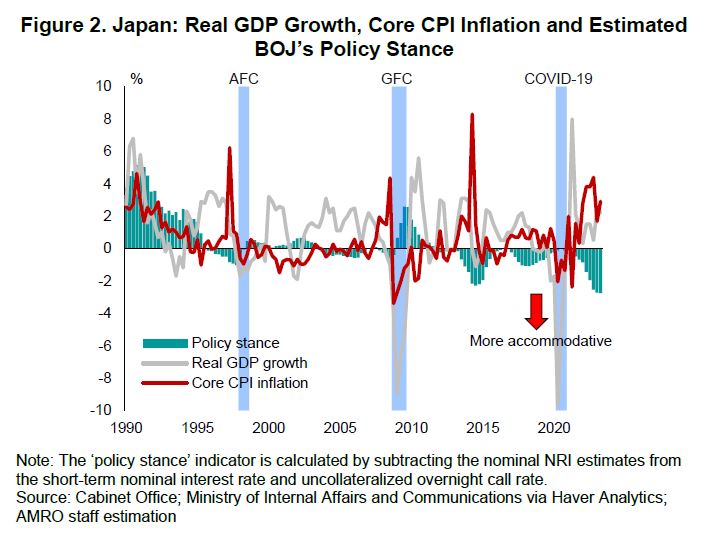

If the BOJ’s monetary policy stance is measured as the difference between short-term policy rates and equilibrium interest rates, namely the r-star in nominal terms, the BOJ’s policy stance appears even more accommodative despite persistently high inflation (Figure 2).

The widening gap between current policy rates and the estimated r-star calls for a gradual adjustment of the BOJ’s ultra-easy monetary policy. Hence, the BOJ’s exit from the negative interest rate and YCC policy was timely, allowing the short-term policy rate to revert to its traditional role in managing inflation and anchoring inflationary expectations.

Such gradual policy normalization is pivotal for the BOJ to mitigate the risk of abrupt monetary tightening to bring elevated inflation down to 2 percent, while creating policy space to implement easing measures in response to future economic shocks.

Following the exit from the negative interest rate and YCC policy, the BOJ should promptly transition its policy regime to the conventional monetary policy framework and respond to secular changes in wage-inflation dynamics. This entails adjusting interest rates to align with economic activity and price outlooks, while also providing clearer guidance to market participants regarding its policy stance.