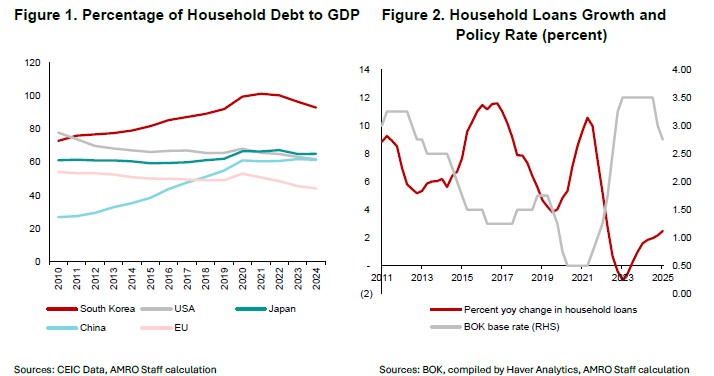

Over the past decade, Korea’s household debt has ranked among the highest in advanced economies (Figure 1). In response, the authorities have maintained vigilance, implementing a series of macroprudential measures to mitigate financial stability risks arising from the rapid increase in the household debt-to-GDP ratio.

A key initiative in this effort is the Debt Service Ratio (DSR) framework, introduced in 2018 to assess a borrower’s ability to service debt based on annual income. Initially applied at the institutional level, the framework required financial institutions to limit exposure to high-risk borrowers based on DSR thresholds. For example, commercial banks were required to cap loans with DSRs between 70 and 90 percent at 15 percent of their total lending, and those exceeding 90 percent at just 10 percent. While this institutional-level approach curbed some excessive lending, it did not fully address individual borrowing behavior. Certain borrowers could still restructure loans or temporarily reduce outstanding balances to meet DSR threshold.

To address these limitations, the authorities expanded the DSR framework in 2021 to apply directly to individual borrowers. Under the revised rules, individuals with total household debt exceeding KRW 100 million were required to comply with DSR limits not just for new loans, but also for refinancing and top-up loans. Additionally, the assumed loan maturity period for credit loans in DSR calculations was reduced from 10 years to 7 years in 2021, and to 5 years in 2022. These changes effectively raised estimated annual debt service obligations and thus the DSR, limiting borrowers’ eligibility for further credit. These measures ensured a more balanced allocation of responsibility between lenders and borrowers, reinforcing prudent lending practices.

Phased implementation of stress DSR framework

As Korea navigated the economic challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021, monetary policy was eased to support economic activity, inadvertently fueling a surge in household loans (Figure 2). However, with inflation on the rise, the Bank of Korea began raising interest rates in August 2021. The subsequent sharp rise in interest rates increased repayment burdens, particularly for borrowers with floating-rate loans, exposing the vulnerability of the system to interest rate fluctuations.

In response, a stress DSR framework was introduced in early 2024. By adding a stress margin to the base lending rate for new floating-rate loans, banks could better assess borrowers’ repayment capacity under adverse financial conditions. This move not only tightened borrowing requirements for floating-rate loans, but also encourages a shift toward fixed-rate loans, offering borrowers more predictable payments and improved financial planning.

To ensure a smooth transition, the stress DSR framework is being implemented in three phases.

- Phase 1 (February-August 2024): Applied to mortgage loans issued by banks with the addition of a stress rate of 0.38 percentage points to the actual lending rate.

- Phase 2 (September 2024-June 2025): Expanded coverage to include both mortgage and credit loans from banks and mortgage loans from non-bank financial institutions. The stress rate rises to 0.75 percentage points for loans in non-metropolitan areas, and to 1.2 percentage points for loans in the Seoul metropolitan area.

- Phase 3 (starting July 2025): Will cover all household loans, applying a stress rate of 1.5 percentage points in metropolitan areas, while maintaining the 0.75 percentage point rate in non-metropolitan regions for an additional six months.

Continued monitoring crucial

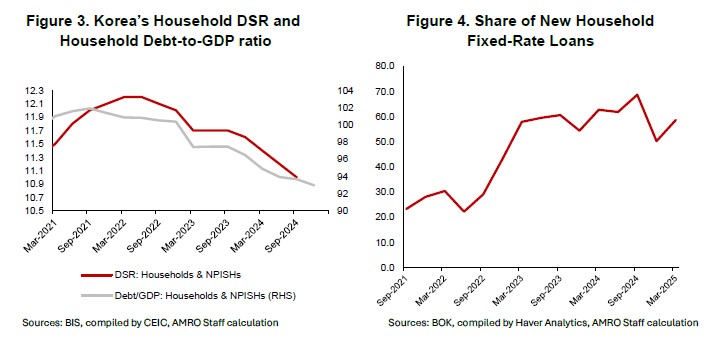

Initial results are encouraging. Since early 2024, both the aggregate household DSR and the household debt-to-GDP ratio have continued to decline (Figure 3), indicating a reduction in repayment burdens and moderation in household leverage. The rebound in the share of fixed-rate loans in early 2025 (Figure 4) may further suggest borrower’s possible responsiveness to the tighter lending standards, despite a more accommodative interest rate environment.

Looking ahead, continued monitoring will be crucial as the stress DSR framework progresses. While early results are positive, the full effects on credit quality may take time to materialize due to the typical lag between loan origination and repayment risk. In addition, the stronger application of the DSR could weigh further on the already sluggish real estate market in non-metropolitan areas. The use of differentiated stress rates across regions reflects an effort to manage rising household debt, while limiting the burden on less active housing markets outside the capital region.

Korea’s experience with the DSR framework—especially the recent adoption of the stress DSR—demonstrates a proactive and adaptive approach to household debt management. As global financial conditions evolve, Korea’s model offers valuable inisghts for other economies seeking to enhance the effectivness of macroprudential tools in addressing risks stemming from high levels of household debt.