After being postponed in 2015 and 2017, Japan’s consumption tax was finally raised from eight to ten percent in October 2019. Most food items are exempted.

This long delay was mainly due to concerns that the tax hike could trigger a sharp economic contraction, similar to what happened in 1997 and 2014.

The previous painful experience prompted the world’s third-largest economy to employ measures to minimize demand fluctuations this time round.

To relieve the financial burden faced by households, the government pledged nearly half of the extra revenue to fund social welfare programs, including early childhood education.

Consumers were eligible for temporary rebates on purchases made using electronic payments, while low-income and households with children aged up to three and half years were eligible to purchase vouchers at a discount to pay for goods and services at stores and hospitals.

Impact on private consumption less severe

How different was the impact of the 2019 consumption tax hike from previous tax hikes?

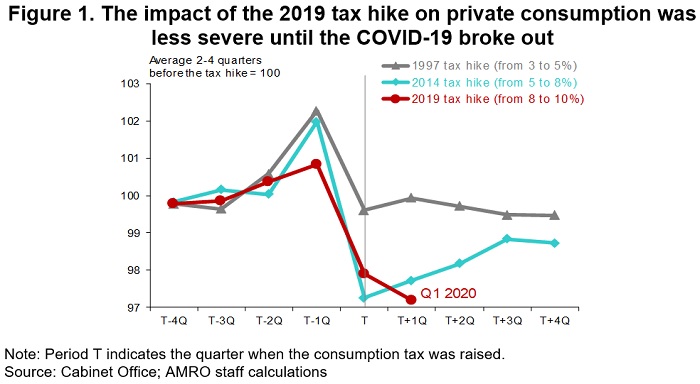

GDP data suggests that the impact of the recent tax hike on private consumption was less severe than that of the 2014 tax hike, with smaller fluctuations in consumption.

Compared to the tax hikes in 1997 and 2014, consumption did not spike as much before the tax was raised in October 2019. Subsequently, consumption contracted by 2.9 percent over the October-December period in 2019, the first quarter following the tax hike. The decline was 4.8-percent during the April-June period in 2014.

Consumption was also adversely affected by supply disruptions due to the typhoons last October; otherwise, the decline in consumption would have been even smaller.

Compared to 2014, the swing in private consumption was less than in 2019, partly due to a modest increase in last-minute spending (Figure 1).

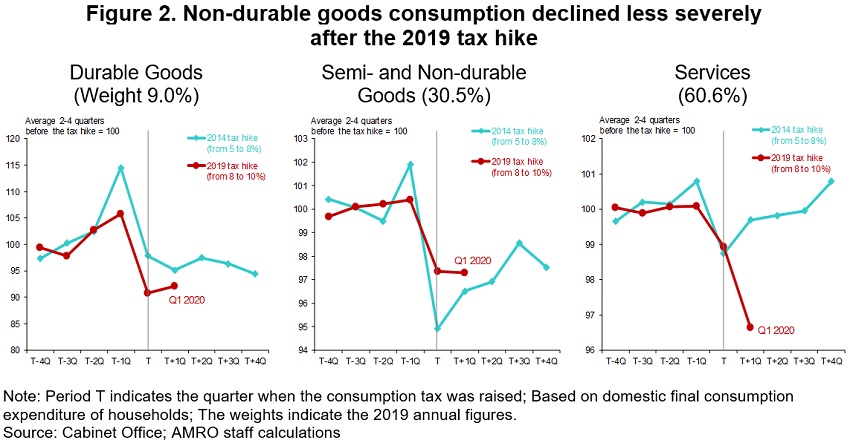

After the tax hike, consumption of durable goods such as automobiles and household electrical appliances slid as sharply as in the 2014 tax hike, while semi- and non-durable goods consumption declined less severely, partly due to the unchanged tax rate on food and beverages. Services consumption remained less volatile in Q3-Q4 2019 around the tax hike (Figure 2).

Overall, the government’s countermeasures succeeded in managing demand fluctuations to some extent.

Rebound disrupted by the COVID-19

The sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 derailed the recovery in domestic demand. The implementation of containment measures disrupted and weakened economic activities. As a result, Japan’s services consumption dove further in Q1 2020, the second quarter following the tax hike, leading to a 0.7-percent contraction in private consumption (Figure 1, 2).

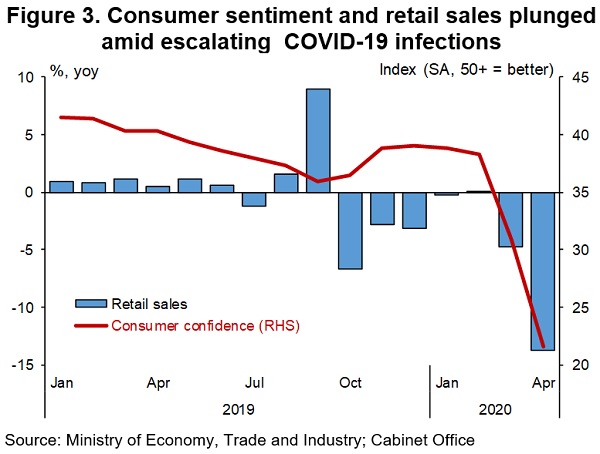

Consumer sentiment plummeted to an unprecedented level in April. Retail sales growth dipped into the negative territory again in March and plunged deeper in April, caused by the declaration of a nationwide state of emergency (Figure 3).

Against this backdrop, the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office recently cut the 2020 growth forecast for Japan to -5.7 percent.

Was the tax hike implemented at the wrong time, given Japan’s struggles to avoid a prolonged recession?

We do not think that was the case.

No analyst, economist or policymaker can guarantee an optimal timing, ex-ante. A postponement in the consumption tax hike yet again would have made it extremely difficult to implement in the foreseeable future.

How can Japan ride out this economic storm?

Against the backdrop of a recession, global pandemic, and trade tensions, the so-called Abenomics’ “three arrows” of monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and structural reforms have a lot to do to revitalize the economy.

Firstly, the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ’s) easy monetary policy should be maintained under the current framework of massive asset purchases with yield curve control.

Despite the narrowed policy space, the BOJ should stand ready to ease further if necessary. It should make sure to support smooth financial intermediation for businesses. The BOJ’s monetary policy communication remains vital with its strong forward guidance.

Secondly, fiscal policy can be used flexibly and skilfully.

Formulating massive economic relief packages to support those affected by the pandemic is inevitable. Well-targeted spending and swift implementation toward vulnerable households and industries are essential for the efficacy of the packages.

Once the pandemic subsides, the government needs to recalibrate its fiscal consolidation plan to revive the long-term fiscal sustainability.

As the COVID-19 pandemic exposes weaknesses in the Japanese economy, the third arrow of structural reform should be accelerated to address these challenges.

A recent survey by the Japan Association for Chief Financial Officers revealed that workers in 40 percent of Japanese companies continued to return to the office to seal paperwork with their personal stamps (“hanko”) while telecommuting. In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity. Digitalization of the economy should be prioritized to deregulate remote medical consultations, support telecommuting, and promote e-commerce, e-learning, e-government and other online services.