The global tax reform, scheduled for implementation in 2024, aims to reduce tax competition between countries and discourage multinational enterprises (MNEs) from engaging in profit shifting for tax avoidance. As of end 2023, 10 out of 14 members in ASEAN+3 have joined the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) and embraced its two-pillar approach, alternatively known as BEPS 2.0.

Pillar One aims to reallocate taxing rights from low-tax jurisdictions to market jurisdictions where sales and users are located, irrespective of MNEs’ physical presence. Pillar Two ensures that MNEs contribute their fair share of tax revenues to countries where they generate profits by imposing a global minimum corporate income tax.

Many ASEAN+3 economies have actively taken steps toward implementing Pillar One and Pillar Two by assessing the impact of BEPS 2.0 on their economies and making amendments to their domestic laws and tax treaties. The OECD estimates that reallocating tax rights to market jurisdictions under Pillar One will benefit developing countries, as they can apply domestic corporate income tax to the reallocated taxing rights, generating an additional US$17-32 billion in annual tax revenue. Pillar Two, designed to raise global revenue by enforcing a 15 percent minimum effective tax rate on large and profitable MNEs, could yield an additional US$200 billion in annual global tax revenue.

Pillar One is expected to take effect in 2025. Although the consensus-based agreement on profit allocations is still undergoing extensive negotiations, over 100 jurisdictions, including ASEAN+3 economies, have strengthened and streamlined their tax codes and administrations to impose indirect taxes, such as Value Added Tax (VAT) on e-commerce businesses to seize revenue opportunity prior to the implementation of Pillar One.

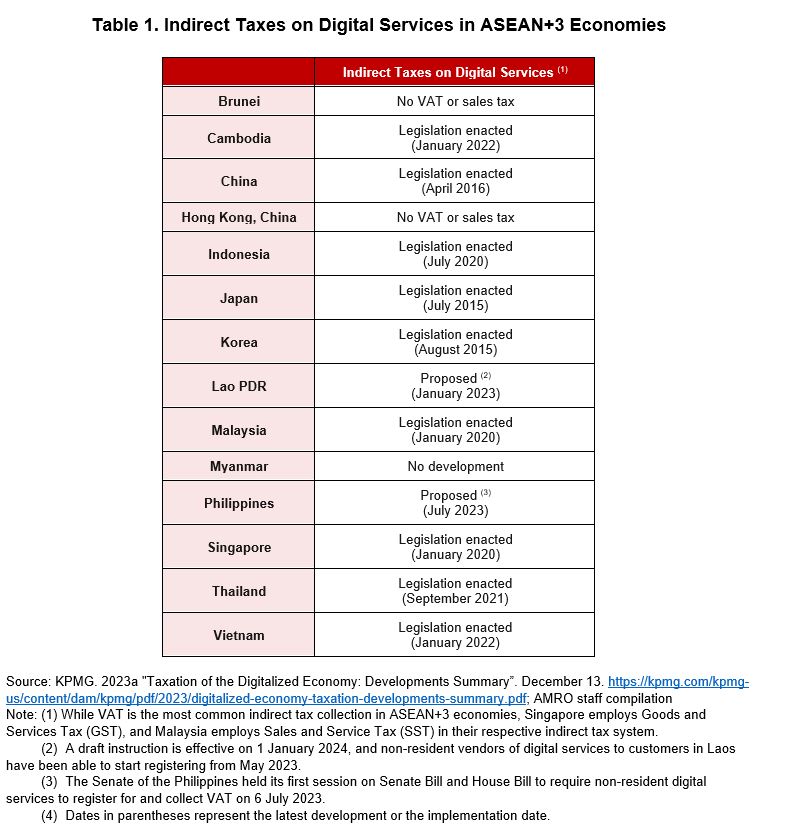

China, Japan and Korea have taken the lead in mandating non-resident digital businesses and e-commerce marketplaces to register with local tax authorities and are collecting VAT on their sales. Most ASEAN economies with indirect taxes have progressively extended their tax collection to cover e-commerce, and all ASEAN+3 economies are scheduled to commence indirect tax collections from digital service providers in 2024 (Table 1).

For the implementation of Pillar Two, several ASEAN+3 economies have started to review and amend their domestic laws to apply a top-up tax on profits. This is to ensure an effective corporate income tax rate of 15 percent for large MNEs operating in their countries.

Korea and Japan are the first two economies to have enacted legislation for the full implementation of Pillar Two in 2024. Vietnam, which hosts over one hundred MNEs, also passed a resolution in November 2023 to implement Pillar Two starting from January 2024. Hong Kong and Singapore, which have large MNEs operating in their economies and also serve as the regional headquarters for other large MNEs, are preparing their domestic tax systems for the implementation of global tax reforms starting in January 2025. Thailand and Malaysia have also committed to adopting top-up tax under Pillar Two starting from 2025. While ASEAN+3 jurisdictions endorse the implementation of a global minimum tax, they are also exploring potential tax and non-tax measures to maintain FDI competitiveness.

The two pillar solution is expected to reduce the gap in effective tax rates across jurisdictions, providing an opportunity for countries to consider tax incentive reforms aimed at attracting genuine FDI. In addition to reducing tax competition, attracting MNE investments will now require a stronger emphasis on non-tax measures, including macroeconomic and political stability, competitive human capital and labor costs, strong rule of law, institutional consistency, and efficient physical and digital infrastructure.

A delay in or failure to comply with these internationally agreed tax reform proposals could result in foregone tax revenues and relocation of investment to other locations in the medium to long term. However, the escalating complexity of both pillars has raised concerns among developing ASEAN economies about potential compliance costs that may outweigh the expected income gains. To tackle this uncertainty, governments must thoroughly assess the potential impact on their countries’ economic and investment landscapes and work collectively to find a common approach to advance BEPS 2.0, before incorporating these rules into domestic tax laws and new policies.

Technical assistance from the OECD and relevant international organizations are available to ensure a swift and proper implementation of the legal and administrative adjustments to comply with rules of the two pillar solution. More importantly, formal discussions between investors and the state should be held regularly and in a timely manner to reduce compliance costs. And tax authorities should provide sufficient trainings for officials and businesses to ensure efficient implementation and minimize potential disputes.

In the long term, ASEAN+3 economies can enhance their revenues by adopting equitable global tax standards, while refining both tax and non-tax policies and stepping up on capacity-building efforts. Regional economies can further leverage their digital landscapes and technology to streamline tax administration and strengthen revenue collection, fostering a more dynamic and sustainable economic environment for years to come.