Since 1958, two years after joining the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Argentina started to actively engage the Fund to request financial help, strongly driven by its rooted structural vulnerabilities. To-date, Argentina has benefited from the Fund’s assistance via 22 arrangements. The most recent two arrangements to tame the country’s prolonged economic challenges amid political uncertainty were made through the Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) program in June 2018 and the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) in March 2022.

With most of its arrangements under the SBA program, Argentina makes for a unique global financial safety net (GFSN) case study. Given the IMF’s role as public goods for the functioning of the international monetary system, the Argentine case has sparked a lot of debates in relation to its default experiences, its exceptional access1 to IMF’s loan programs, and the government’s weak commitment in implementing the designed program as well as the role played by the IMF in the context of the GFSN.

The 2018 Stand-by Arrangement

The 2018 SBA is the country’s 21st arrangement with the Fund. Argentina requested a 36-month of exceptional access, amounting to around USD 50 billion or 1,110 percent of Argentina’s quota. In 2018, after a 15-year hiatus, Argentina came back seeking financial assistance after experiencing a shift in market sentiment and an ill-fated confluence of factors, including a sharp decline in agricultural production and export caused by severe drought; tightening global financial conditions; and some internal policy slippages that culminated in a wide range of economic distortions. The requested facility aims to: (i) restore market confidence; (ii) protect the society’s most vulnerable; (iii) strengthen the central bank’s credibility; and (iv) alleviate pressure on the balance of payments.

However, after the fourth review by the IMF (out of twelve expected), Argentina’s economic condition did not improve and instead went through the most challenging time. The government finally cancelled the program in July 2020, 14 months after it started, without success. It is widely known that weak public finances have been central to Argentina’s economic problems, destroying market confidence. The program was inadequate in addressing deep-seated structural challenges, resulting in its failure.

The 2022 Extended Fund Facility

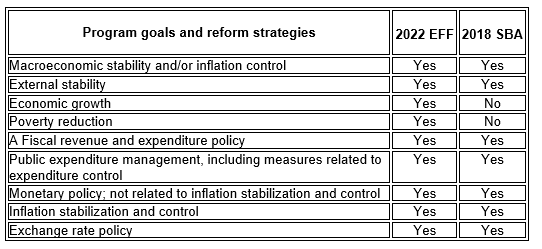

Despite this failure, the country took the same approach in March 2022, requesting an extended fund facility2 from the IMF for 30 months with around USD 45.5 billion or 1,001.3 percent of Argentina’s quota. As a preceding request, the facility sought to strengthen balance of payments and improve public finances as well as to cover USD 43 billion in total of the outstanding obligations to the IMF arising from the 2018 SBA. To achieve the program’s goals and strategies, which are different from previous the SBA reflected in table below, a set of quantitative performance criteria and a long list of prior actions and structural benchmarks under the EFF arrangement was laid out, mainly focusing on elements to enhance growth and resilience as well as to encourage investments. Interestingly, the strategy to strengthen external resilience and reserve buffers includes trade policy-related reforms aimed at supporting trade surpluses, encouraging net exports and long-term capital inflows, and paving the way to re-enter international capital markets.

General lessons for CMIM

Recognizing Argentina’s unsuccessful program in using IMF’s resources, what can the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM), ASEAN+3 region’s financial safety net, learn from the Argentine case?

The IMF summed up that the failed Argentina’s 2018 SBA was caused by several factors, including the insufficient robustness of the program’s strategy and conditionality to address the deep-seated structural problems, the disproportion of the government’s ownership which led to overly optimistic forecasts and weakened the program’s prospects, and the erosion of political support due to an election during the program.

Given Argentina’s long story and intricate problems, including the last failed program, it is fair to see a wide range of views on the prospects for Argentina’s current program. No doubt, it is challenging to deal with a vulnerable country, in terms of identifying, preventing, and resolving complicated problems efficiently. It may spark the question on rationality if the IMF, as public good, is heavily exposed to a single country when many other vulnerable economies may need its resources.

The CMIM can draw some lessons learnt from this case study.

First, ensuring the program’s robustness and contingency plan is essential to control the delicate balance between the program’s prospect and political viability. It is crucial for the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO), as the international organization established to support the implementation of the CMIM, to sharply assess the requesting country’s most basic economic and financial issues, especially those with deep-rooted structural issues, based on a strong qualification framework. Capturing a prospective political landscape in case of highly uncertain political environment is also critical to support program’s robustness. A lending program in crisis financing is doomed to fail, in case there is no strong political support in the borrowing country from new political ruler after general election or presidential election.

Second, tailoring a program to the country’s specific circumstances, including non-traditional measures, is critical for a relevant and streamlined CMIM program. Regarding the program’s conditionality, it is necessary to address the country’s specific vulnerabilities and focus on the areas under the authority’s direct or indirect control. After all, a sensitivity test against several different assumptions is crucial to ensure the program’s robustness in all possible circumstances.

Third, balancing program’s ownership between the authorities of the borrowing country and the lending party, such as the IMF or CMIM members, to strengthen program credibility will be key to securing program effectiveness. One key consideration for a CMIM program is to recognize the balance of the requesting country’s ownership and capacity to implement, while paying close attention to the lending party’s concerns. For this, it is critical to have discussions with as many relevant parties as possible while giving due care to program credibility.

Fourth, it is important to have an effective external communication. This will ensure that the program is widely accepted by the public and bring out catalytic effects, particularly when uncertainty surrounds the country. For any CMIM program, a clear communication to the public is indispensable.

Lastly, it is worthwhile to consider a hybrid instrument in CMIM financing available for both precautionary and actual difficulties. Under highly uncertain situations, it would be challenging to differentiate between crisis time for actual difficulties from a near-crisis time for a precautionary arrangement. This is instrumental for CMIM members to consider. It will be also desirable to have a readily available fund to increase the financing certainty.

1“Exceptional access” is access to the Fund’s general resources for member, under any type of Fund financing, which typically exceeding the normal annual limit of 145 percent of the member’s quota, or a cumulative limit (net of scheduled repurchases) of 435 percent of the member’s quota, subject to the Fund’s Exceptional Access Policy.

2The EFF was created in view of the fact that balance of payments problems could have structural origins and require a longer period of adjustment. Consequently, the EFF offers longer repayment periods than those under credit tranche policies, but requires more action in the structural area than is typical of SBAs.