By Chaipat Poonpatpibul, Li Wenlong, Simon Liu

Another version of this article was published on the China Daily on December 13, 2017

Also available in Chinese (中文稿)

China’s non-financial corporate debt has reached record high. While this is unlikely to lead to a systemic crisis in the short term, it is still a worrying sign for the economy.

The ratio of corporate debt-to-GDP was as high as 155 percent in 2016, according to an estimate by the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO). Since the beginning of 2017, this has started to flatten and the growth in the corporate debt began to slow due to stepped-up regulation and supervision by the authorities and declining leverage in the financial sector. However, challenges remain as the improvement has resulted from higher nominal GDP growth rather than a decline in corporate debt.

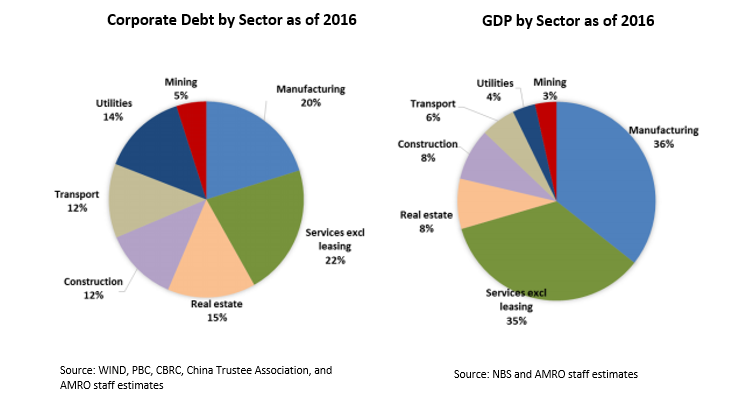

Based on solvency and liquidity indicators as well as nonperforming loan ratios, the bulk of corporate debt is not risky. Nonetheless, the problem is concentrated and more severe in some sectors where credits have built up while profitability and repayment capacities have declined, as noted by AMRO in its recent study titled “High Corporate Debt in China: Macro and Sectoral Risk Assessments”. Those are prioritized sectors under the investment-led growth model, such as state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in steel, mining, utility, transport, and manufacturing, as well as some private firms in real estate and construction. Manufacturing accounts for the most significant shares of total corporate debt at 20 percent, followed by real estate (15 percent), utilities (14 percent), construction (12 percent) and transport (12 percent).

Drivers behind high and rising corporate debt

Multiple factors have pushed China’s surging corporate debt over the past decade.

After the global financial crisis (GFC), China’s economy was fueled by credit expansion, especially to SOEs. While this led to a significant increase in investment and spending, and in turn, higher growth, investment efficiency and profits were eroded. In particular, maintaining high levels of production of SOEs led to overcapacity and losses, especially in sectors which experienced a cyclical downturn.

China’s high savings rate has also contributed to high debt financing. At 46 percent of GDP, China has by far the highest savings rate among large economies. However, channels to mobilize these savings to meet firms’ investment needs are still limited. Hence, the bulk of investment funding is still done through banks in the form of loans.

Another major reason for the rapid increase in corporate debt is China’s rapid urbanization, which has spurred infrastructure and real estate projects that are relatively credit intensive.

Who finances the risky sectors?

Despite the declining efficiency and repayment capacities of borrowing firms, some financial institutions might still think “high risk, high return”.

Bank loans are still the main source of financing for corporates, but their share of total financing has declined. Meanwhile, the shares of bonds and shadow banking loans have increased sharply to 20 percent and 16 percent respectively, especially in the vulnerable sectors such as mining, real estate, and construction.

Although shadow banking loans have higher interest rates, they are more flexible and have become a more popular form of financing. Investors also earn higher interest rates on these products. Bond financing is also likely to increase further against the backdrop of the bond market development.

Compared to large banks, smaller banks have a higher concentration of loans in the riskier sectors. They have been more aggressive, not only in issuing bank loans, but also in lending through shadow banking.

Reform call

The focus of corporate debt deleveraging should be on the reduction of debt in SOEs and the vulnerable sectors.

The authorities need to further push ahead with comprehensive structural reforms that help increase investment efficiency. SOE reform should be geared toward market-based mechanism and strengthened governance. Successfully cracking down on “zombie” companies and further reducing overcapacity will help improve profitability and market-driven investments, and hence bring down bad debt.

The capital markets should be further developed to provide more sources of corporate equity financing and reduce the reliance on debt financing. Debt-to-equity swaps should be based on best market practice and proper legal frameworks to effectively help reduce debt.

As for sectoral policy, macro-prudential measures in the real estate sector should be maintained to rein in growing debt. In the utilities, transport, and construction sectors, Public-Private Partnership (PPP) can be an alternative source of financing. To boost private firms’ confidence, there should be greater transparency in local government financing vehicles as well as increased financial disclosure. More importantly, sufficient fiscal resources are needed to support vulnerable workers during the deleveraging process.

Stress tests on assets and liabilities can help pinpoint potential losses. Regulators should then require banks with significant risks to raise capital and improve their liquidity profiles. Strengthening the buffers of financial institutions with high exposures to the vulnerable sectors can help mitigate risks to financial stability. At the same time, tight regulation and the implementation of the Macro-Prudential Assessment (MPA) should be maintained. That will help rein in risk-taking behaviors through off-balance sheet activities including certain types of shadow banking loans as well as interbank borrowing.

Corporate and financial sector data should also be strengthened to support more accurate and thorough risk assessment and monitoring.

Debt sustainability can be seen as an important indicator of the health of the economy. The world’s second-largest economy should take bold actions to curb surging corporate debt and show the market and investors that its growth does not come at high prices.