Singapore’s population is aging rapidly. Already the oldest nation in ASEAN and the fourth oldest in ASEAN+3, over 16 percent of Singapore’s population is aged 65 and above. This demographic reality stems from a combination of low fertility rates—among the lowest in the world—and an exceptionally high life expectancy. The growing elderly population could weigh on future growth and increase fiscal burden. This article explores how Singapore has addressed these challenges and what more can be done.

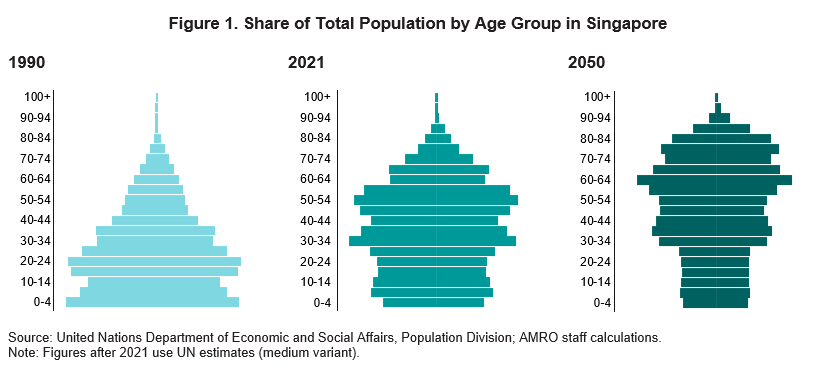

The proportion of Singapore’s working-age individuals has been shrinking since the early 1990s. Despite efforts to bolster the labor force through the recruitment of foreign talent, its decline is expected to continue. By 2050, the nation’s population pyramid will see a pronounced shift, with a much smaller working-age base supporting a significantly larger elderly population (Figure 1). The support ratio—the number of working-age individuals supporting each elderly person—is projected to drop from five to fewer than two. This would intensify the fiscal burden and weigh on economic growth, as the potential productivity gains of a smaller workforce may not fully offset the rising costs of supporting a growing elderly population.

Yet, Singapore has not been idle in addressing these demographic shifts. Its excellent healthcare system has contributed to not only a longer lifespan but also healthier aging. Initiatives such as the Healthier SG program, launched in 2022, emphasize preventive care and community health management, while the Agency for Integrated Care has improved support for aging populations. These efforts, alongside sustained investments in healthcare quality, are crucial in managing the demand for fiscal resources as the population ages. Notably, using a prospective measure of aging—defining “old” as having fewer than 15 years of remaining life expectancy—the healthy lifespan of the individuals can be extended considerably beyond the traditional definition, and the share of elderly in Singapore would be nearly half of the current measure by 2065.

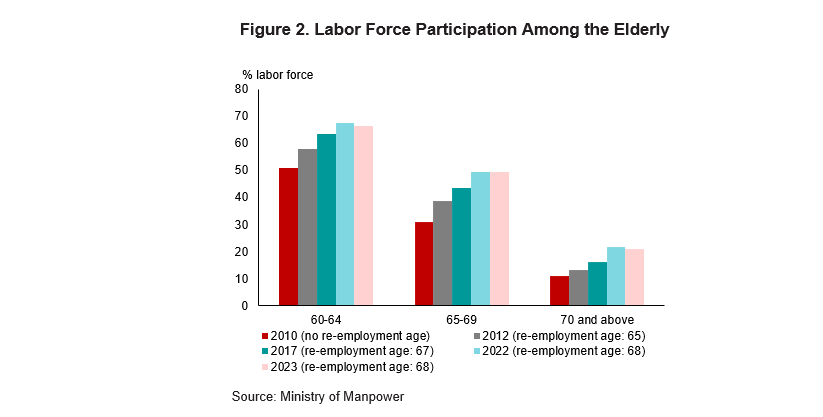

Singapore has also proactively embraced the “longevity dividend,” empowering and encouraging older citizens to remain productive members of the workforce. The retirement age has gradually risen from 55 in 1988 to 63 today and will increase further to 64 by July 2026. This increase, alongside the introduction of a re-employment framework, has encouraged the continued employment of older workers. Today, 67 percent of those aged 60-64 and 50 percent of those aged 65-69 are employed, giving Singapore one of the highest elderly labor force participation rates globally (Figure 2).

However, more can be done to help the aging workforce. By 2030, Singapore will become a “super-aged” nation, with over 21 percent of its population aged 65 and above. Despite progress in increasing labor force participation among the elderly, many elderly individuals face financial insecurity due to inadequate savings and gaps in pension coverage under the Central Provident Fund, leaving many reliant on low-skilled jobs for supplemental income. Others struggle to adapt to the demands of a rapidly digitalizing economy. Workplace age discrimination also remains a concern, with older workers often reporting fewer opportunities for training and advancement.

Digitalization and automation present opportunities to address these challenges. By reducing the physical demands of work, these technologies can enable older workers to remain productive in their work or transition into some supervisory roles or pursue new jobs. However, a strategic approach is essential—integrating these technologies must go hand-in-hand with promoting continuous learning and reskilling initiatives. Additionally, a more flexible labor market that expands part-time and gig economy opportunities, can boost workforce participation while addressing the unique needs of an aging population.

Increasing workforce participation among women also remains crucial. While Singapore has made strides, women’s participation still lags behind men across most age groups. In parallel, Singapore must continue leveraging foreign talent to address skill gaps. The measured approach during the COVID-19 pandemic, which prioritized resident employment while recalibrating foreign worker inflows, demonstrated the value of flexibility. Going forward, policies like the Complementarity Assessment Framework (COMPASS) should evolve to meet the needs of a changing labor market while maintaining social cohesion.

Singapore must also bolster its social safety net to ensure that its elderly population, especially those at risk of financial hardship, are adequately supported. Nearly one-third of older adults anticipate financial struggles, with nearly half fearing a lower standard of living as they age. Enhanced welfare measures will not only protect vulnerable seniors, but also help ensure social dignity and financial security for these seniors.

With the right strategies, Singapore can transform its aging population from a demographic challenge into a catalyst for inclusive growth—all while striking a delicate balance between economic resilience and social cohesion.