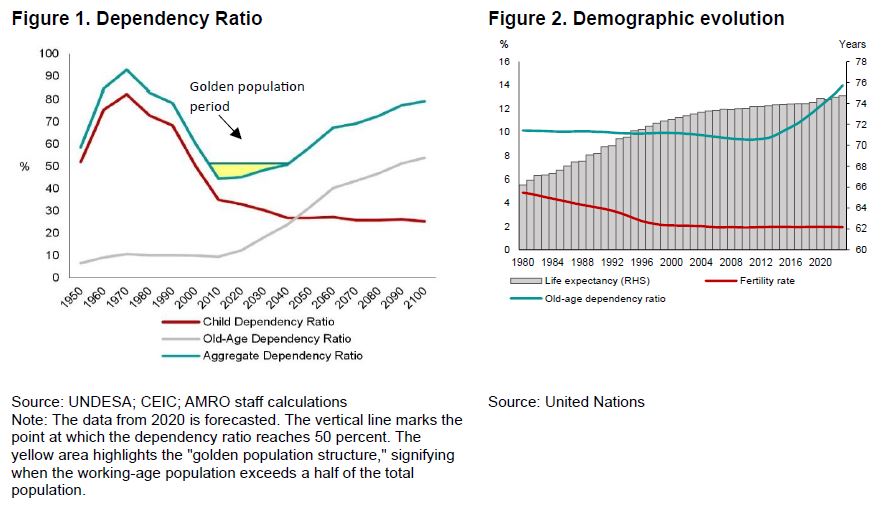

Vietnam is at a pivotal juncture in its demographic evolution. The country is transitioning rapidly from the “golden population structure” period toward aging and aged society. This transition has significant implications for the country’s economic development and the welfare of its citizens.

Vietnam entered the golden population period in 2007. Its abundant workforce helped contribute to the country’s remarkable economic growth over the past decade. Unfortunately, while the country was harnessing the large size of its population, it was also experiencing a dramatic decline in its fertility rate that resulted in a rapid aging of its population.

Due to this swift change in the demographic structure, Vietnam’s golden population structure is expected to end around 2040 or even earlier (Figure 1).

In 2021, Vietnam was ranked sixth in the ASEAN+3 region in terms of the share of senior citizens, with approximately 9 percent of its population aged 65 years and older. This proportion continued to rise due to a sharp decline in fertility rates since the 1970s (Figure 2).

The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) forecast that it would take 18 years for Vietnam to transit from an aging nation into an aged society by 2036 (United Nations Economic and Social Council, 2022). This timeline is shorter than some of Vietnam’s regional peers such as Thailand (20 years), Indonesia (22 years), Malaysia (24 years), the Philippines (30 years), and Japan (24 years).

Challenges facing Vietnam’s economic development and population wellbeing

Despite being in the golden population period, the Vietnamese economy has not fully reaped its advantages. While the country has welcomed foreign investment and experienced rapid growth, it is still grappling with ascending the global value chain.

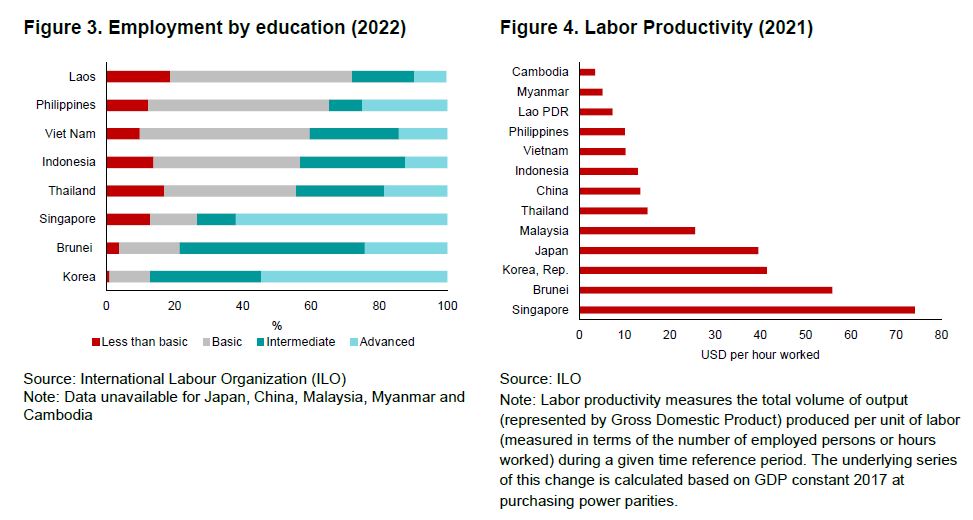

Approximately one half of Vietnam’s workforce held only basic qualifications, while around 40 percent had intermediate or advanced qualifications at the end of 2022. In terms of the number of highly educated workers, Vietnam slightly trailed its regional peers such as Thailand and Indonesia, and significantly fell short of Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, and Korea (Figure 3).

In terms of the quality of workforce, a significant share of Vietnamese people remains concentrated in the low productivity sectors of agriculture, forestry, and fishery which accounts for about 27.5 percent of the total workforce.

Although workers in Vietnam are more productive than workers in Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Myanmar, their productivity still lags behind workers in regional manufacturing-based peers such as Thailand and Malaysia. (Figure 4).

Additionally, while the working-age population earns low wages, many old Vietnamese people are struggling to earn extra income to meet their post-retirement living expenses. One of the reasons is attributed to the limited coverage of the old-age pension.

As at the end of 2022, only 38 percent of Vietnam’s working-age population participate in the pension scheme of the social insurance system. The number remains well below Vietnam Social Security’s goal of expanding the contributor coverage to 60 percent of the labor force by 2030.

Consequently, many Vietnamese elderly individuals may not have adequate post-retirement income and will not receive social insurance benefits by the time the country reaches the aged society.

Leveraging golden population period while preparing for aging

The existing policies may not be adequate to address the rapid aging of the population. The Vietnamese government has implemented several measures in recent years such as the promotion of marriage before the age of 30 along with having kids before the age of 35, and an increase in the retirement age to 62 and 60 for males and females, respectively.

More incentives can be introduced, such as a special reduction of personal income tax for working mothers, social housing for young couples, or the improvement of availability and quality of childcare centers.

At the same time, the government should allocate more resources to boost labor productivity. Low-skilled labor should have greater access to higher education and vocational training, especially in high value-added industries. Labor in the rural area and agricultural sector should be trained to diversify their jobs and expertise.

Lastly, social security measures should be strengthened. Efforts should be directed toward increasing the economic independence of the senior population. The coverage of the old-age pension should be expanded to include workers in the informal sector and late contributors. The healthcare services and long-term care insurance such as old-age nursing homes, should be further developed. Additional policies or financial products that incentivize working-age populations to save for retirement should be introduced.

Transitioning from a golden population structure to a successful aging society necessitates a strategic approach from the Vietnamese government. Policies should not only address the immediate concerns of an aging population but also prepare for long-term challenges.