Over the past several decades, global value chains (GVCs) have expanded rapidly, providing the impetus for trade, investment and growth in many small and open developing economies, including in the ASEAN+3 region. GVCs lower the cost of production and improve the quality of a product by providing an opportunity for economies to specialize in a particular segment of the value chain of a product in which they have a competitive advantage. Developing economies can therefore participate in the production of a technologically advanced product through the global value chain, and then move up the value chain, as they become more developed. In the region, the GVCs developed in the 1980s when Japanese MNCs outsourced the production of different components of the final products to different countries in the region. It expanded rapidly in the 2000s after China became a member of the WTO in 2001, with China at the apex of the value chain processing the final products, and the neighbouring countries producing intermediate inputs that feed into the final products.

However, by linking the economies together through trade into an interlocking production network, the GVCs have also become the channel through which real shocks in any one economy are propagated across the network to other economies. This can be seen during the Great Recession in 2009-10 when demand in Western economies collapsed in the wake of the Global financial crisis, and the shock is propagated to the regional economies. Border barriers, such as tariffs and other protectionist measures, are also transmitted across national borders through the global value chains as producers try to pass the higher cost of the tariffs up or down the value chain to other producers and suppliers.

The latest statistics recently released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on Trade In Value-Added (TiVA) with data updated up to 2015 suggest that the region’s favorable fundamentals, such as growing middle class and rapid urbanisation, have underpinned the structural shifts in the regional value chains. In particular, the rapid growth in regional consumption and investment, especially after 2011, has led to growing intra-regional final consumption and absorption of value-added exports within the region. As a result, the ASEAN+3 region has become a key source of final demand in itself, accounting for 45 percent share of total exports in 2015, up from 35 percent in 2011.

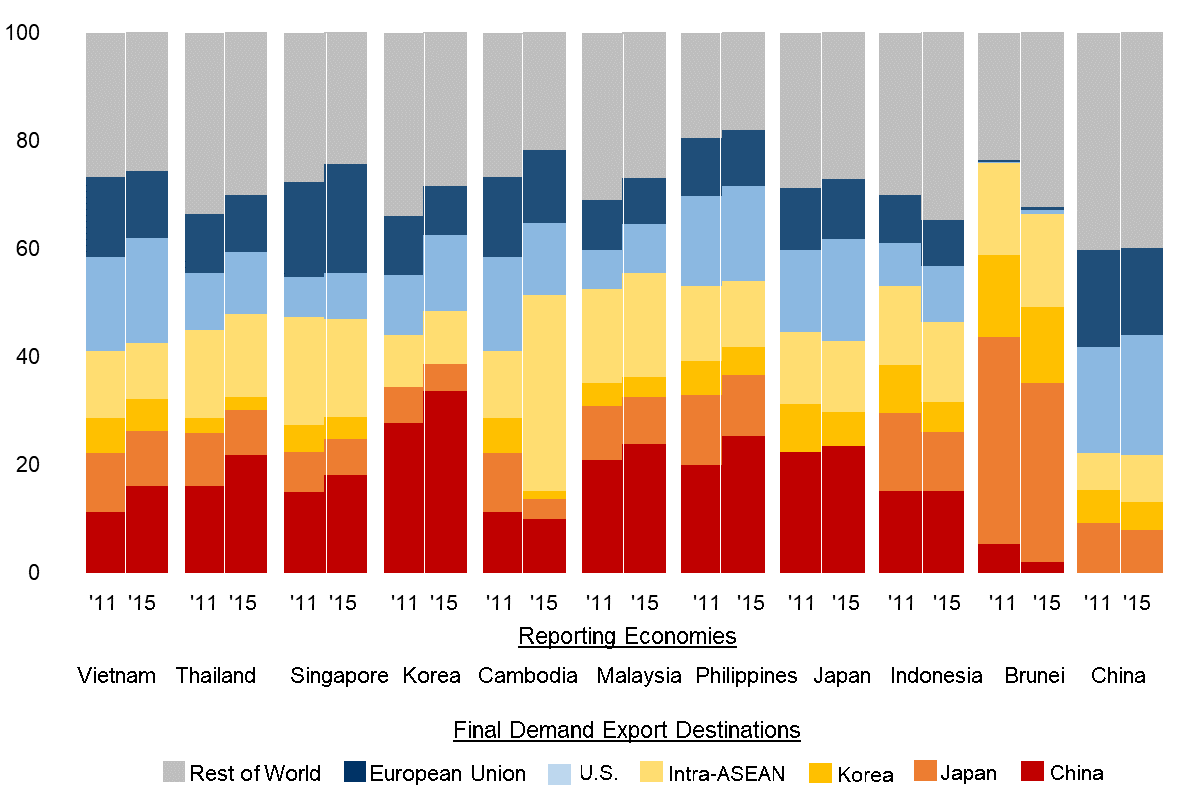

For several manufacturing exporters, such as Vietnam, Thailand, Korea, Cambodia, and Malaysia, the share of regional final demand has increased since 2011 (Figure 1). For commodity exporters (Brunei and Indonesia), the share of foreign final demand from the rest of the world has increased significantly, indicating diversification in export markets. For other economies, the shares have remain largely unchanged.

Figure 1

Share of the Region in Value-Added Exports of Selected ASEAN+3 Economies

(% Share of Reporting Economies’ Total Exports)

Source: OECD and AMRO staff calculations

The implication of such structural demand shifts is that the downside risks and spillover effects from U.S. trade protectionism through the GVCs on the regional economies are much lower than before.

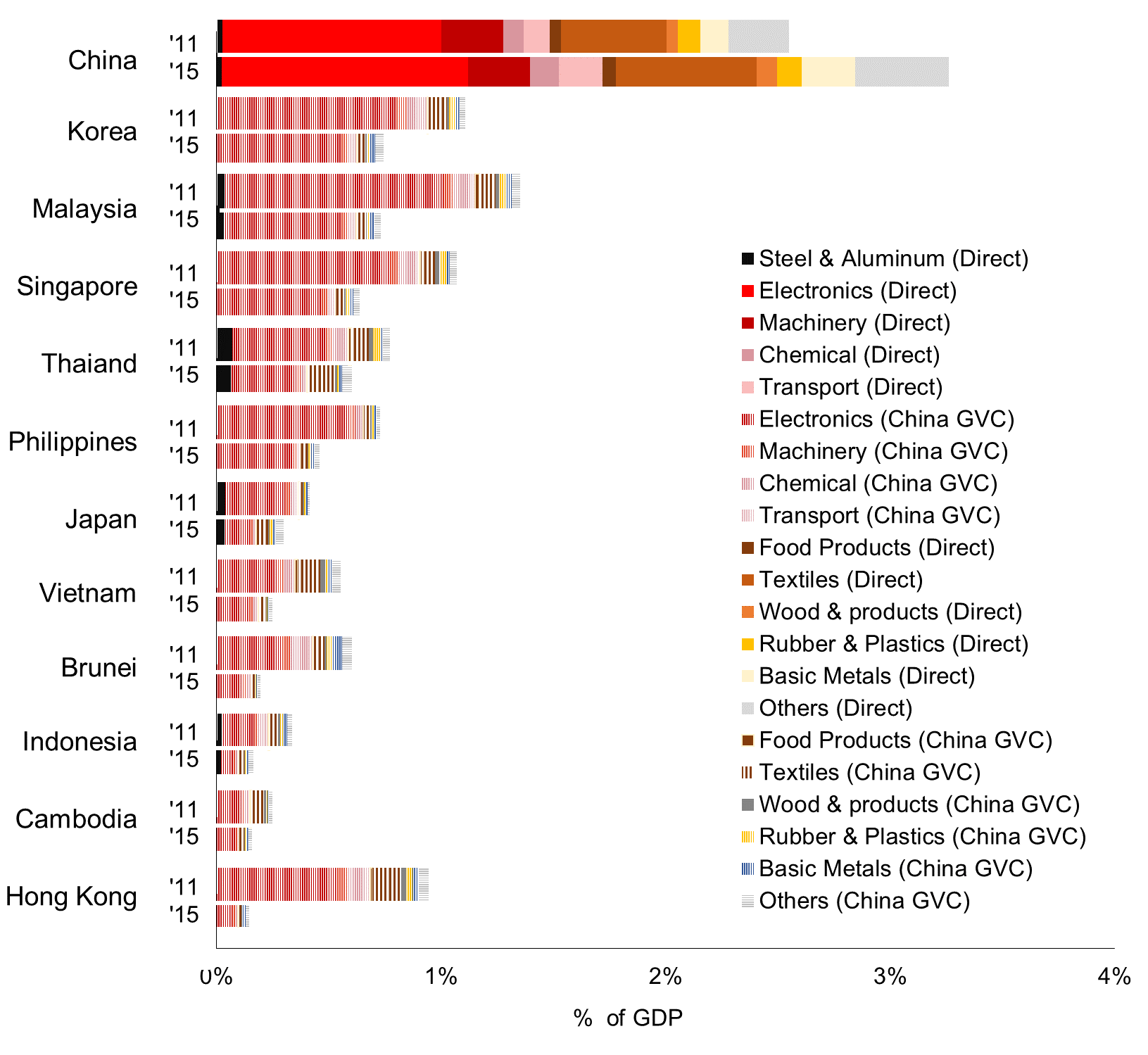

In the current trade conflicts, trade actions by the U.S. on China include 25 percent import tariffs on USD50 billion worth of Chinese high tech manufactured goods, and 10 percent import tariffs on USD200 billion worth of Chinese goods ranging from mineral to food and textiles. Using the updated 2015 TiVA statistics, AMRO’s estimates of the export exposure of the region to U.S. trade actions targeted directly at China’s exports, but excluding potential auto tariffs, suggest that China’s export exposure to the U.S. trade actions has increased to 3.3 percent of GDP, from 2.6 percent in the 2011 TiVA. (Figure 2) The corresponding export exposure of regional economies (excluding China), amounts to at most 1 percent of their respective GDP, which is around one percentage point lower than that in the 2011 TiVA. This includes both direct effects, and the indirect effects via GVCs.

Figure 2

Regional Export Exposure (Including the Spillover Effects via GVCs) on U.S. Trade Actions Targeted Directly at China’s Exports, but Excluding Potential Auto Tariffs

Estimated Using OECD’s Trade In Value-Added Statistics 2015

Source: OECD and AMRO staff estimates

This underscores the notion that the restructuring of GVCs, as well as structural shift in demand, especially consumption by the rapidly rising middle class, has underpinned the expansion in intra-regional trade in final demand within the region. The region’s favorable fundamentals and ongoing efforts to build capacity and connectivity to foster greater economic integration and growth augur well for the region. These longer term trends toward greater regional integration can enhance resilience against shocks by reducing the spillovers effects from trade protectionists actions by Western economies.