Image: Ismail Sadiron Pictures / Shutterstock.com

The COVID-19 pandemic brought widespread concern and financial distress to individuals and businesses − and ASEAN+3 governments responded with a wide array of macro-financial measures. Support measures include debt relief and regulatory forbearance; in Malaysia, loan repayment assistance schemes were made available to borrowers who were adversely affected by the pandemic. Together with cash handouts, wage subsidies and pre-retirement pension withdrawals, loan relief has played a critical role in helping households and small businesses get through the worst of the pandemic.

From a financial stability perspective, however, the regulatory forbearance and repayment assistance is masking the true quality of loans as banks are not required to classify loans as non-performing so long as the loans are under moratorium or the repayment assistance scheme. But as the economic recovery sets the stage for the unwinding of relief measures, can the Malaysian banking sector withstand the resulting increase in loan impairments? The recently published AMRO Annual Consultation Report on Malaysia answered this question by applying a reverse stress test on all domestic commercial banks.

Evolution of Malaysia’s loan repayment assistance

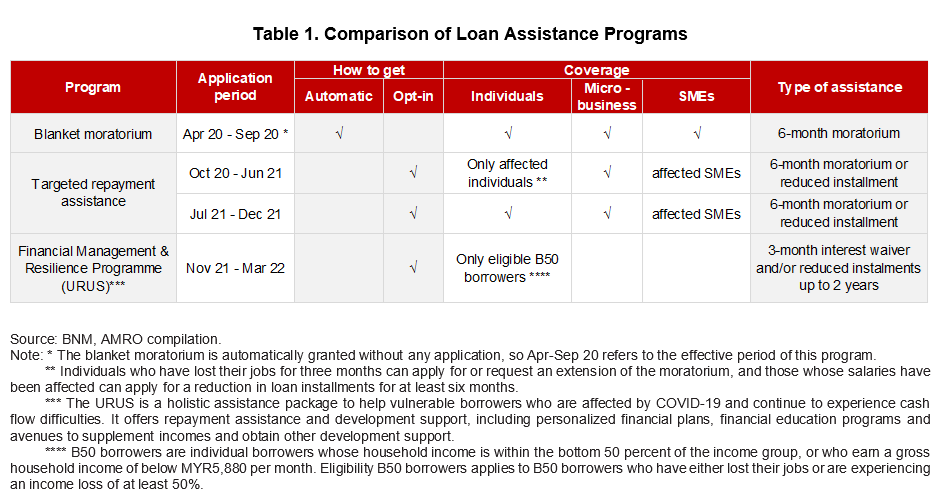

A six-month blanket moratorium on loan repayments was initially provided to all borrowers, with the exception of large corporates, from April to September 2020. The measure was followed by a targeted repayment assistance (TRA) scheme from October 2020, aimed especially at pandemic-affected households, and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) on an opt-in basis. In July 2021, the severe Delta outbreak and the re-imposition of movement restrictions prompted a widening of the TRA to all individual borrowers, albeit still on an opt-in basis, until the end of 2021.

Malaysia’s high vaccination coverage has enabled the country to reopen despite the Omicron wave in early 2022. And so, in line with the economic recovery, the TRA is being phased out since the beginning of 2022 while retaining the repayment assistance schemes for eligible low-income borrowers under the Financial Management and Resilience Program (URUS) (Table 1).

During the six-month blanket moratorium period, 77 percent of households and 68 percent of MSME received loan repayment assistance. With the economy improving, loans under assistance dropped sharply to 16 percent of household loans and 22 percent of MSME loans, as of June 2021. However, the outbreak of the Delta variant and the broadening of the TRA have pushed up loans under assistance to 36 percent of household loans and 37 percent of MSME loans by November 2021. After the TRA expired, loans under assistance sharply fell to 3-6 percent as of July 2022 for some large banks.

How this effort affects banks’ performance

With the repayment assistance in place, banks do not need to downgrade their affected loans to non-performing loans (NPLs). As a result, the NPL ratio was masked and remained at around 1.5-1.6 percent in the past two years, similar to its pre-pandemic level. The NPL ratio gradually increased to 1.7 percent in June 2022, and may further increase towards the end of 2022, given that most loans will no longer be under the TRA.

The good news is that banks have been closely monitoring their loan quality and building up provisions as a cushion to prepare for the likely increase in the NPL ratio. In June 2022, loan-loss provisions covered 1.8 percent of total loans and 108.5 percent of NPLs, rising substantially from 1.3 percent and 83 percent in 2019, respectively.

It remains crucial to know at which NPL level, banks will have trouble in maintaining the capital asset ratio (CAR) above a certain distress threshold.

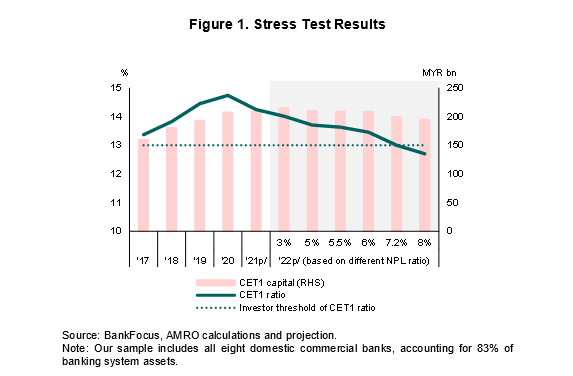

The logic of our reverse stress test is that, the higher the estimated NPL ratio compared to the actual NPL ratio, the less likely it is that the bank would lose its sound financial position. Our results show that banks’ NPL ratio would need to rise to 7.2 percent in order for banks’ Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio to fall below the perceived investor threshold of 13 percent (Figure 1).

Given that Malaysia’s economic recovery has regained momentum, this estimated NPL ratio can be seen as a tail risk. Since Q2 2022, loans under assistance have been much smaller than at the end of 2021. Most of the remaining borrowers will have the financial ability to service their loan repayments according to banks, suggesting only a small amount of loans will eventually be downgraded to NPLs. For loans not under repayment assistance, the increase in the NPL ratio will also be limited, given the continuing recovery of large corporates and MSMEs, and the improved household conditions, suggested by the rising consumer confidence and declining unemployment rate. Therefore, the CET1 ratio in 2022 across banks is expected to be higher than our perceived investor threshold.

Nevertheless, the risks of global stagflation and a resurgence of vaccine-resistant COVID-19 infections are significant. If materialized, they could again affect borrowers’ repayment capacity and further undermine the banking sector’s performance. Authorities should therefore insist that banks remain vigilant in their monitoring and assessment of credit risks while providing a more targeted and calibrated support to households and businesses.