This article was first published as an op-ed in The Business Times on October 6, 2022

Disruptions to the global flow of goods during the pandemic are dissipating.

Delays in supplier delivery times for the global manufacturing sector have receded from the highs in 2021, and have weathered the disruptions from the Russia-Ukraine war and COVID-19 lockdowns in China this year. Freight rates for container, dry and liquid bulk shipping and air cargo, have likewise fallen from their record highs.

These developments are good news to producers and consumers worldwide. Abating supply chain disruptions means that production processes can resume smoothly, reducing the pressure on global inflation, including in the ASEAN+3. For policymakers, moderating inflation would allow for greater focus to support the economic recovery. But are the bottlenecks clearing up for good?

Origins of the global supply chain crisis

To answer this question, we look back to mid-2020 when Europe and the United States (US) emerged from COVID-19 lockdowns, and their pent-up demand met with severely constrained production capacities across the world. Worldwide movement restrictions and the massive pandemic stimulus packages in advanced economies led to an e-commerce boom amid labor, equipment and raw material shortages.

The supply-demand imbalance had squeezed shipping networks. Maritime ports, which handle the bulk of internationally traded goods, recorded long vessel delays worldwide.

In the US, outdated port and landside infrastructure struggled to cope with the unprecedented import volumes. The logjams led to long vessel queues, especially at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach — the main gateway for US imports.

At the same time, the widening of both Europe’s and the US’ trade deficit with Asia led to a pile-up of containers in the key Western markets and a shortage in Asia, which consequently held back seaborne exports from the region amid mounting vessel delays.

Widespread shortages in equipment, warehouse spaces, and manpower were also blamed for hampering the flow of containerized shipments at major ports globally.

On top of these issues, dislocations brought about by the Russia-Ukraine war and China’s dynamic zero COVID policy this year have brought new challenges to global supply chains.

Cooling global demand provides relief to supply chain frictions

Against the backdrop of a potential worldwide recession, cooling global demand is gradually alleviating supply chain pressures.

Concerns of a cargo rush as the COVID-19 lockdown in Shanghai—a global manufacturing hub and host to the world’s busiest container port—was lifted in June 2022 have yet to materialize. Instead, the cost of shipping a forty-foot container between Shanghai and Los Angeles has continued to decline, to about USD3,250 recently from over USD10,500 at the beginning of 2022.

This downward trend in freight rates is occurring as global trade volumes slow amid softer demand.

Seasonally adjusted import volumes in the US fell by 8 percent between March and July 2022 while those of the United Kingdom were down by nearly 9 percent. March was when headline inflation in the West rose more sharply than in preceding months. Euro area import volumes have held up so far but consumer imports dipped slightly in June.

Worries of a deepening growth slowdown and clearing work backlogs are prompting businesses to slow down the pace of inventory build-up. Retailers and manufacturers had stocked up on raw materials, component parts, and finished goods as the supply chain disruptions worsened last year.

But supply chain struggles remain

To be clear, global imports have not collapsed, so large volumes continue to put a strain on supply chains. Global container freight rates, for instance, are still over three times higher than their 2019 levels despite a 50 percent decline this year.

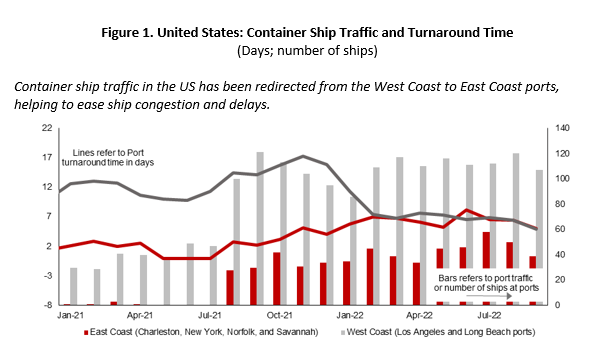

In the US, port congestion has eased partly because of a shift in ship traffic to the East Coast, giving ports in the West Coast some breathing space to clear logjams (Figure 1). But as ship traffic is redirected to East Coast ports, container ships are also staying 2-9 days longer there from just 3-4 days a year ago.

Indeed, supply chains are still confronted with numerous hazards. Labor shortages across layers of the supply chain, lack of warehouse space to accommodate new shipments, and empty containers piling up at US and Europe ports are some of the persisting constraints to supply chains.

Structural issues aside, disruptions to raw material supply, factory output, and logistics may also arise from China’s stringent COVID-19 policy, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and extreme weather disturbances.

Building resilience and flexibility in supply chains

While the supply bottlenecks are not likely to go away any time soon, supply chains are being reshaped toward greater resilience and flexibility.

According to a McKinsey survey conducted in the spring of 2022, businesses continue to build inventories, but more have also adopted dual-sourcing strategies and regionalized supply networks over the past year. Supply chain digitization is likewise picking up.

Such efforts are believed to be paying off; this year’s geopolitical disruptions were found to have had limited impact on companies that have taken resilience measures.

But developing supply chain risk management capabilities can take years. For now, global supply chains are finding relief from easing global demand.

Sources: MarineTraffic and AMRO.

Note: Turnaround time measures the length of time from a vessel’s arrival at the port anchorage to departure from the port.

For more up-to-date and granular port-level information, kindly visit the AMRO Supply Chain Slider.