Monetary Policy in Asia since the Pandemic

“Anchoring Stability amid High Uncertainty”

Remarks by Dong He1 , AMRO Chief Economist, at The Chinese University of Hong Kong Public Lecture

Introduction

It is a great pleasure to be here at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Thank you for the invitation and for the opportunity to reflect on how monetary policy in Asia has evolved since the pandemic.

In the past five years, we have lived through a global pandemic, the sharpest synchronized inflation surge in decades, the fastest global monetary tightening cycle since the early 1980s, and now a world shaped by persistent geopolitical tensions, economic fragmentation, and volatile climate shocks.

For central banks, this has been a period of great uncertainty — about the nature of the shocks hitting our economies, the stability of inflation dynamics, and even the structure of the global economy itself.

These developments force us to confront difficult questions. How do we distinguish temporary disruptions from persistent inflation pressures, in real time? How much can monetary policy lean against supply-side shocks? And how do we preserve credibility and stability when shocks are larger, more frequent, and more global than before?

Against this backdrop, Asia offers a particularly instructive case. While inflation surged to multi-decade highs in the United States and Europe, inflation in ASEAN+3 remained far more contained and far less volatile.

This was not an accident, nor simply good fortune. It reflected two decades of hard-won institutional progress: stronger policy frameworks, deeper financial markets, more flexible exchange rate regimes, and a willingness to act pragmatically when shocks hit.

With this context in mind, I will structure my remarks around three questions. First, how have inflation dynamics in ASEAN+3 changed since the pandemic? Second, how has the region managed spillovers from the most aggressive global monetary tightening cycle in decades?

And third, what lessons does this experience offer for conducting monetary policy in an environment of persistently high uncertainty going forward?

To begin, it is useful to remind ourselves of the fundamental role of monetary policy. In its essence, monetary policy exists to manage economic fluctuations and to preserve price stability. And price stability, at its core, means keeping inflation low and stable.

In recent years, as Agustín Carstens has aptly observed, the role of central banks has taken on even greater significance. In maintaining stability, central banks have become a vital anchor in an increasingly uncertain environment — striving to fulfil their mandates with the public interest and macroeconomic stability at the heart of their decisions.

This naturally raises an important question: how well have central banks in ASEAN+3 delivered on this mandate? And what have inflation and exchange rate dynamics in the region looked like in this period of heightened global turbulence?

Changing inflation dynamics in ASEAN+3

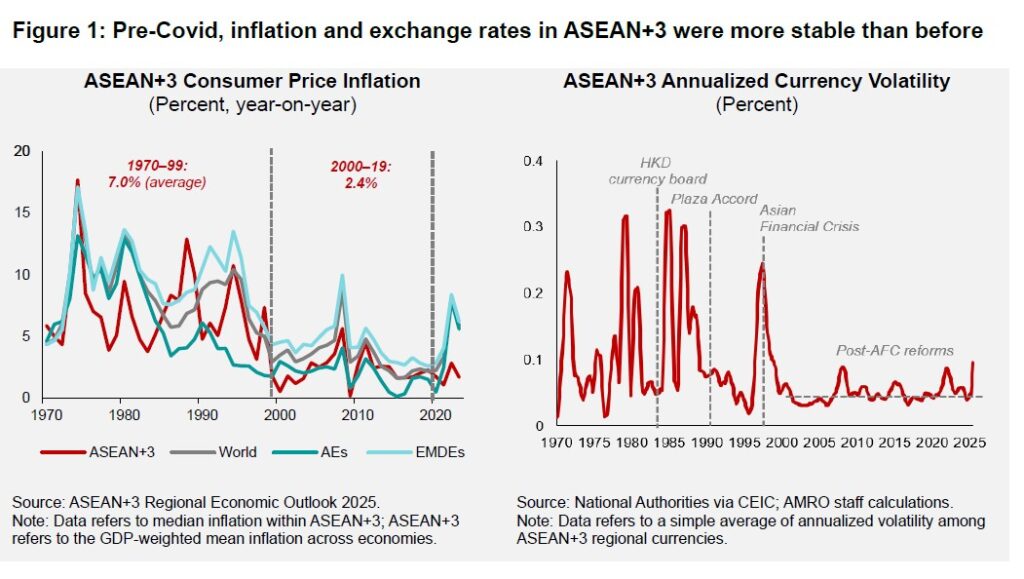

Inflation in ASEAN+3 has declined markedly since the 1970s and 1980s. In the two decades before the pandemic, it averaged just 2.4 percent—less than half the rate seen in the preceding years (Figure 1). Similarly, exchange rates have also become significantly more stable, reflecting the substantial structural reforms after the Asian Financial Crisis that have strengthened macroeconomic fundamentals and financial systems across the region.

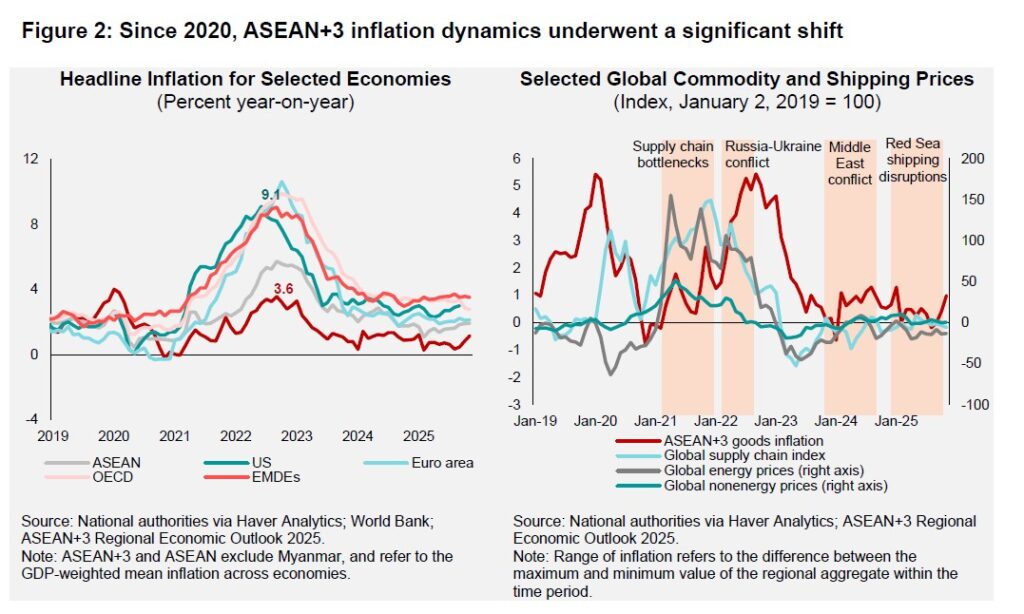

After decades of price stability, ASEAN+3 economies—like the rest of the world—experienced a sharp rise in inflation beginning in 2021(Figure 2). However, the region’s inflation episode differed markedly in scale and volatility.

While inflation peaked above 9 percent in the United States and nearly 11 percent in the euro area, ASEAN+3 inflation peak was much lower at 3.6 percent in 2022 and exhibited far less volatility (Figure 2). The initial surge was driven largely by goods prices and reflected a sequence of global shocks: pandemic-related supply disruptions, reopening-related bottlenecks, the Russia–Ukraine conflict and its impact on energy and food prices, and more recently, intermittent energy price spikes linked to Middle East tensions and shipping disruptions. A key lesson is how quickly, and strongly global commodity prices pass through to inflation in our region.

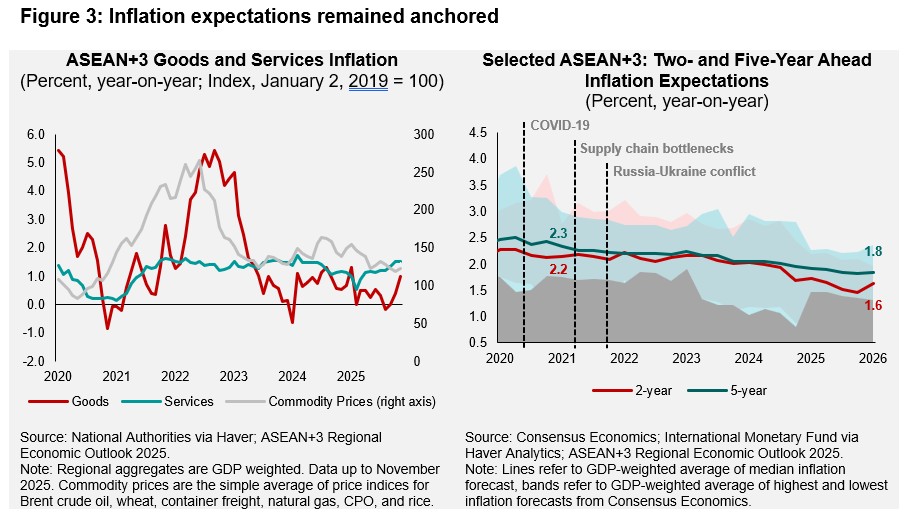

As goods inflation eased, the decline in headline inflation was partly offset by rising services prices. Services prices remained elevated amid post-pandemic adjustments, including tighter labor markets, higher transport costs, and accommodation supply–demand imbalances (Figure 3). Services inflation also proved more persistent, reflecting its labor-intensive nature and the slower adjustment of wages. Importantly, throughout both inflationary and disinflationary periods, inflation expectations remained well anchored—underscoring sustained public confidence in central banks’ commitment to price stability (Figure 3).

Two observations stand out for the period of 2021 to 2024:

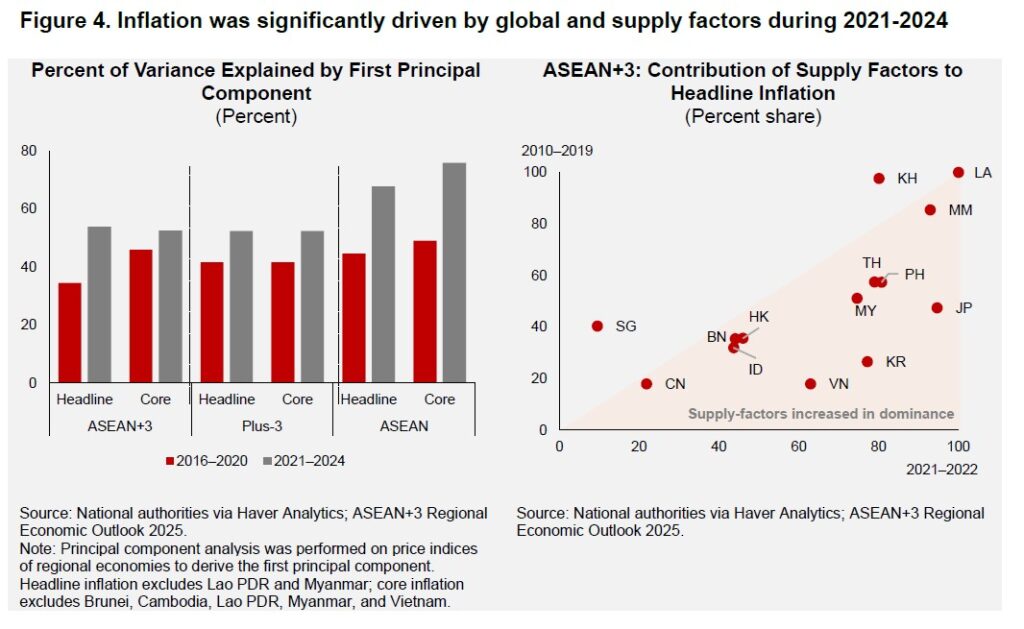

- First, global factors became more prominent drivers of both headline and core inflation across ASEAN+3 (Figure 4).

- Second, supply-side forces played a larger role than in past inflation episodes, with supply chain bottlenecks, labor shortages, and commodity price shocks triggering significant price increases worldwide.

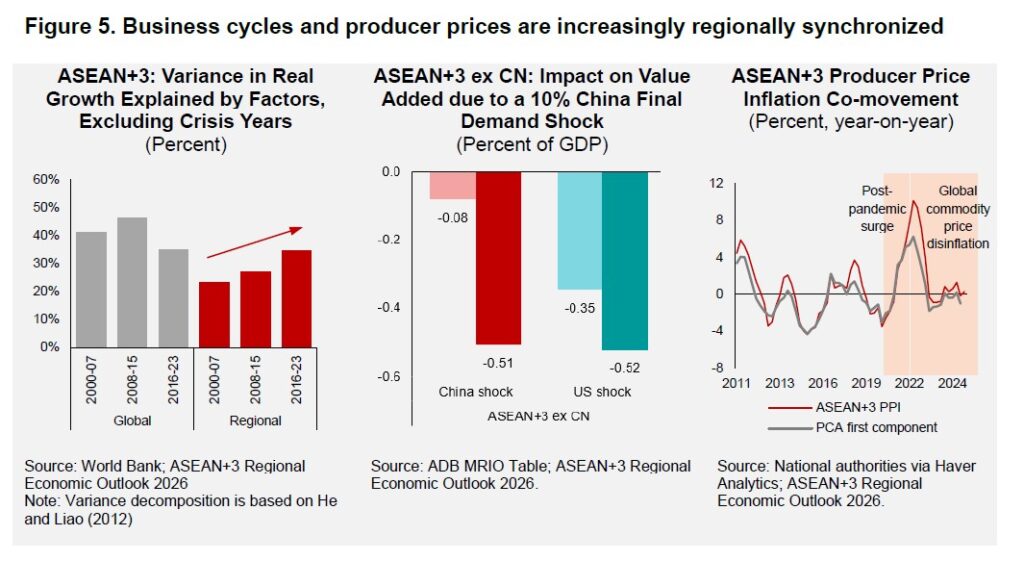

Apart from global factors, ASEAN+3 has become more regionally integrated over the years, driven by the region’s deepening linkages in global value chains and strong intraregional FDI. This has contributed to greater business cycle synchronization, with economic growth now moving more closely together.

Excluding crisis periods, regional developments now explain as much as global shocks in driving growth in ASEAN+3 economies. As trade, investment, and production networks expand, economies are increasingly exposed to shared opportunities, and shared disruptions. In other words, shared production networks also give rise to shared economic cycles.

The magnitude of these linkages has increased materially. In 2000, a 10 percent decline in China’s final demand would have reduced growth in the rest of the region by about 0.1 percent. Today, the impact is estimated to be roughly five times larger. While exposure to US demand shocks remains significant—a 10 percent decline in US demand would reduce regional growth by about 0.5 percent (Figure 5). It is clear that regional shocks have now increased to become equally important as global shocks.

This deeper integration is also reflected in greater inflation synchronization, particularly at the producer price level.

PPI shows stronger regional co-movement, especially during major global shocks. This is consistent with the region’s deeper integration into the regional production network. Shared production networks mean that upstream costs and energy propagate quickly across borders.

Consumer-price synchronization, by contrast, remains weaker – present in ASEAN-5 but largely absent in Plus-3, reflecting the continued importance of domestic and other factors in anchoring consumer inflation dynamics beyond production chain integration.

Managing spillovers from global monetary policy

Even as Asia has become more regionally anchored in terms of real economic linkages, its financial conditions continue to be significantly influenced by global monetary and financial cycles. This reflects the continued importance of the US dollar as the premier international currency for trade and finance in Asia. As a result, global monetary policy shocks can generate meaningful financial spillovers for our region.

During the sharp tightening cycle in the United States and Europe in 2022–2023, concerns emerged about a repeat of past episodes of financial stress – such as the global financial crisis or the 2013 Taper Tantrum.

What transpired was notable. While financial conditions in Asia did tighten—through higher bond yields, weaker equity markets, and weaker currencies against the US dollar—financial systems across ASEAN+3 remained resilient. Financial systems across ASEAN+3 continued to function without major disruptions. There were no systemic instability and no widespread institutional distress.

Two factors explain the region’s resilience.

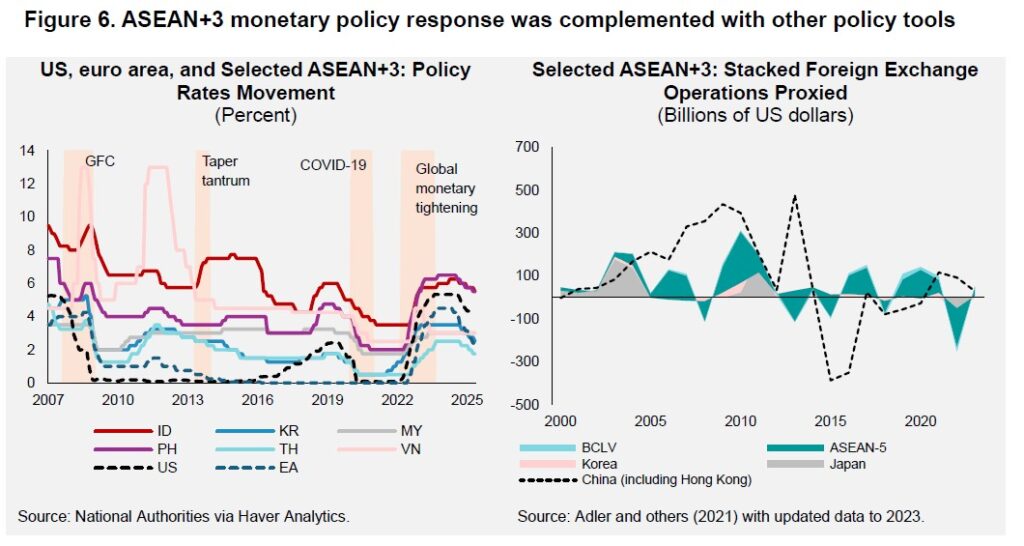

First, a well-calibrated policy mix. During the period of global monetary tightening, ASEAN+3 authorities also tightened monetary policy (Figure 6). However, they did so to a lesser extent than global peers and complemented the monetary adjustment with the use of a mix of policy tools, including foreign exchange interventions, selective capital flow or macroprudential measures, and fiscal support.

Regional policymakers acted earlier and more decisively than in past crises, thus anchoring inflation expectations, containing currency swings, and limiting capital outflows.

High level of international reserves allowed timely foreign exchange interventions to minimize capital flows volatility, giving policymakers additional flexibility to navigate these shocks.

Second, stronger fundamentals and deeper financial markets, built over years, limited systemic risk. Banks in the region entered the tightening cycle with robust capital and liquidity positions. Local-currency bond markets have grown significantly, reducing reliance on foreign-currency funding, and helping weather swings in yield and capital movements. Ample foreign exchange reserves also provided a critical buffer, enabling authorities to intervene and support orderly market adjustments and maintain investor confidence.

Collectively, these factors strengthened the region’s resilience against destabilizing external pressures.

Conducting Monetary Policy under High Uncertainty

Let me now turn to why, in today’s environment of unprecedented uncertainty, we need to rethink how monetary policy is formulated.

We are living in an era of heightened uncertainty of different natures and intensity. The global economy has faced increasingly frequent, large, unfamiliar shocks, while longer-term structural forces, including demographic change and climate risks, are increasing the likelihood of supply-side disturbances.

One of the most pressing global headwinds we face is geoeconomic fragmentation. Trade tensions and policy uncertainty are now widely expected to persist, signaling a departure from the pre-pandemic environment of “low inflation and low volatility”.

In a more fragmented global economy, supply is less elastic, making inflation more volatile and sensitive to shocks. Weaker productivity growth, along with restricted flows of technology and capital, further raises underlying cost pressures, increasing the risk of higher core inflation. Repeated supply shocks also heighten the risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations, complicating monetary policy calibration.

Looking ahead, inflation dynamics will become more complex. We will face greater challenges in identifying the origin and persistence of shocks, and in deciding on the right policy response.

How should we think about uncertainty in monetary policy? Uncertainty has always been part of policymaking, but the intensity and the speed of change today make traditional models less reliable in real time.

A helpful starting point is to distinguish three broad types of uncertainty:

- Structural uncertainty concerns how the economy functions—for example, the strength of transmission channels, the slope of the Phillips curve, or the neutral interest rate.

- Radical uncertainty arises when we cannot specify all possible states of the world or assign meaningful probabilities. The COVID-19 pandemic is a clear example.

- Disturbance uncertainty is about the shocks hitting the economy: what they are, how large they are, and whether they will fade or persist. This was central during the 2021–2023 inflation episode, when policymakers had to judge whether inflation pressures were temporary or persistent.

Under uncertainty, policymakers face three recurring dilemmas:

- Should they respond or look through the shock?

- Should they act now or wait?

- Should they move gradually or frontload policy support?

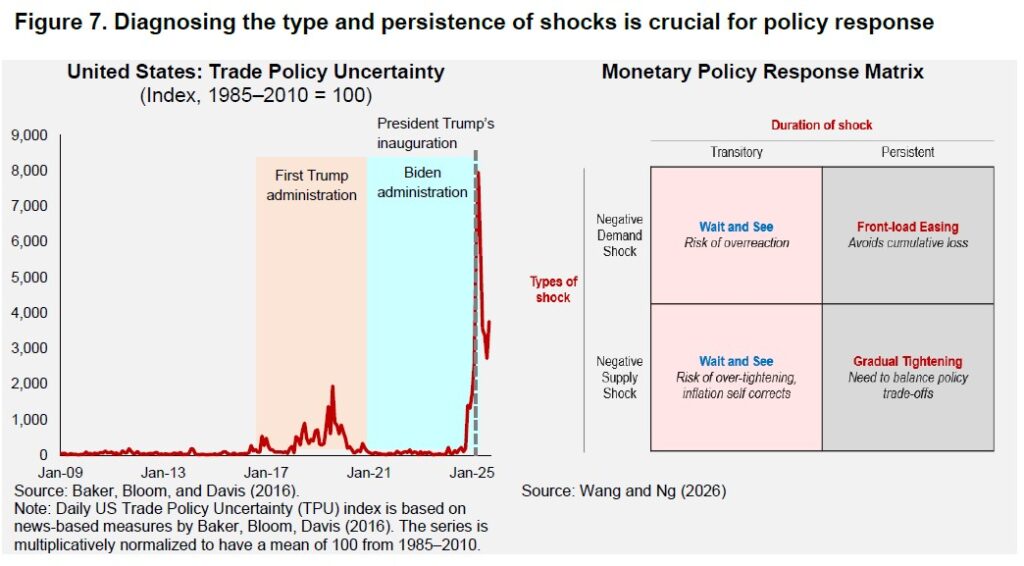

Responding vs looking through shocks: Standard theory suggests that if shocks are temporary and expectations remain anchored, policymakers can look through them. But diagnosing shocks in real time is hard, and the costs of misjudgment are asymmetric (Figure 7). During the inflation surge in 2021–2023, many central banks underestimated persistence and fell behind the curve. Because de‑anchored expectations is extremely costly, policymakers often need to lean toward responding when persistence is uncertain.

Acting early vs preserving policy space: The traditional argument for early action is familiar: policy works with long lags, and delays allow inflation to embed or push economies toward the effective lower bound (ELB). But recent shocks coming from multiple fronts have increased the value of waiting for clearer information. In some situations, patience provides useful signals.

Gradualism vs front‑loading: Gradualism has long been the default approach. It allows learning and limits financial disruption.

However, under uncertainty about persistence, the Brainard principle can reverse: being too cautious may be more costly than acting decisively. Many central banks now use “state‑contingent gradualism”—gradual by default, but willing to frontload when persistence risks or expectation pressures arise.

All three types of uncertainty influence policy, but their relevance differs across the policy cycle.

- Structural uncertainty—about the neutral rate, transmission strength, or inflation dynamics—is mainly handled ex ante through better measurement, model refinement, and strengthening the analytical framework.

- Radical uncertainty calls for contingency planning and scenario exercises alongside the policy framework rather than guide day‑to‑day decisions.

- Disturbance uncertainty must be resolved in real time once a shock hits. Key diagnostic questions—Is the shock demand‑ or supply‑driven? Transitory or persistent?—directly guide whether, when, and how forcefully to respond.

Recent work by AMRO economists2 highlights a threshold: when uncertainty is high, waiting has value—unless shocks are large or persistent.

Four practical insights emerge:

- High uncertainty increases the value of cautious, data‑dependent policy.

- Persistent shocks reduce the value of waiting and support earlier action.

- ELB risks argue for front‑loaded easing.

- State‑contingent communication helps preserve credibility under uncertainty.

To summarize: when uncertainty is high, there is an “option value of waiting.” A cautious approach is justified if shocks look transitory. But persistent shocks call for more front‑loaded action. The core challenge is real‑time diagnosis—distinguishing demand from supply shocks and assessing persistence—which requires stronger surveillance capacity.

Central bank communication may also need to evolve. State‑contingent messaging can explain how policy would respond under different scenarios. Throughout, independence and credibility remain essential to maintain flexibility in navigating these trade‑offs.

The region’s experience during the 2021–2023 inflation episode showed how all three types of uncertainty can overlap:

- Disturbance uncertainty about whether price pressures were supply‑ or demand‑driven and how long they would last.

- Structural uncertainty about whether pandemic‑era disruptions changed transmission channels or inflation dynamics.

- Radical uncertainty, especially early on, about how economies would react to unprecedented policy interventions and supply‑chain disruptions.

As noted earlier, inflation in the region was more moderate and short‑lived than in other major regions. This outcome reflected both structural features—such as high trade openness, competitive retail sectors, and lower service‑sector wage pressure—and timely policy actions combining monetary tightening, fiscal support, and supply‑side measures. Even so, the episode showed how difficult real‑time diagnosis can be when shocks overlap and evolve.

Looking ahead, macroeconomic diagnostic challenges are likely to grow. Several structural forces—demographic aging, trade reconfiguration amid geoeconomic fragmentation, and rapid technological change—will act as slow‑moving supply shocks. Their effects on potential growth, inflation dynamics, and policy transmission will be hard to assess in real time.

At the same time, because monetary policy frameworks differ across the region, the same shock can raise very different diagnostic questions depending on the specific policy setting.

Policy Implications for ASEAN+3

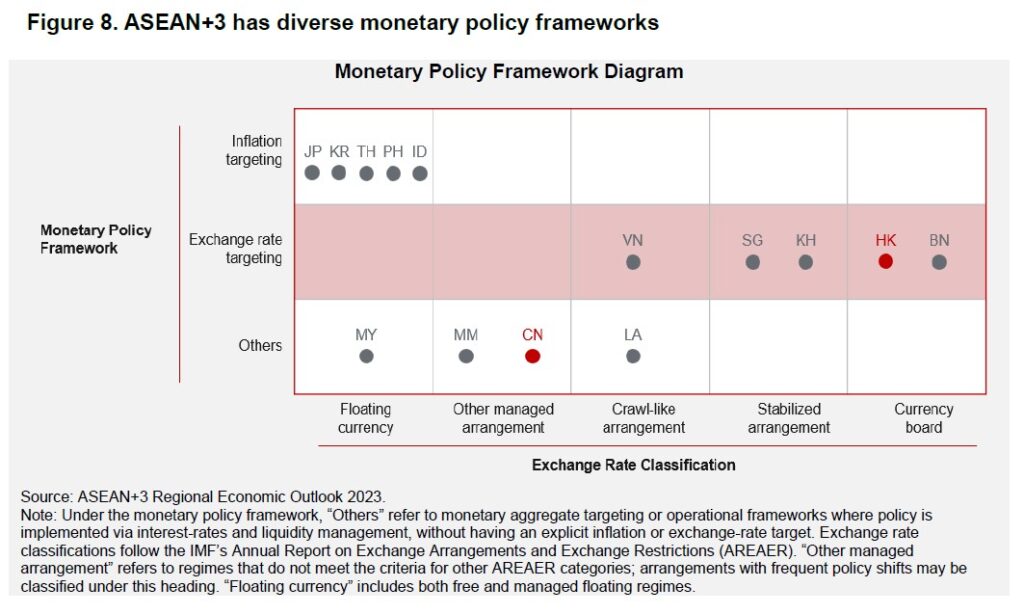

Indeed, monetary policy frameworks are inherently country-specific, shaped by shaped by each economy’s structure, exposure to shocks, and institutional priorities.

In ASEAN+3, this diversity is particularly pronounced (Figure 8). Monetary policy objectives range from inflation targeting to exchange-rate–anchored frameworks, while exchange rate regimes span floating, managed, and even currency board arrangements.

Consequently, the same shock can affect economies very differently, requiring tailored “treatment plans” that reflect each country’s unique conditions and priorities.

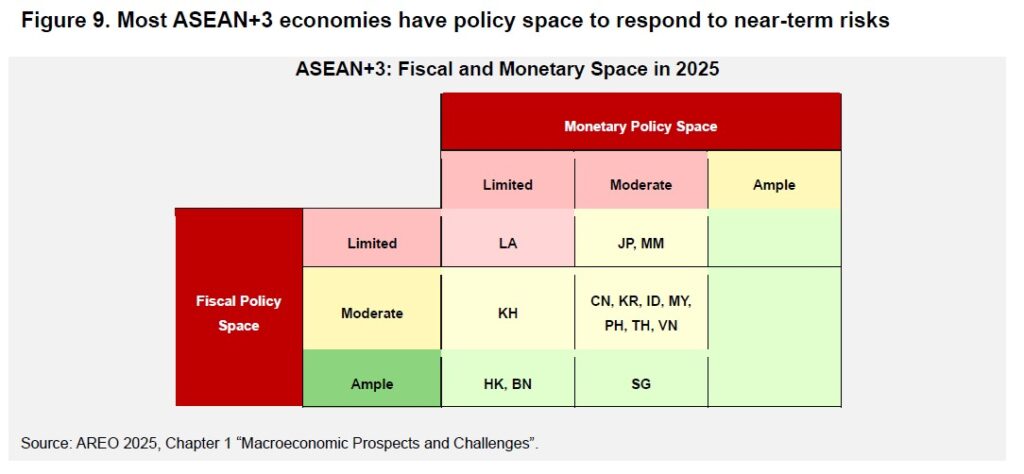

In the near term, moderate fiscal and monetary buffers across most ASEAN+3 economies, together with less acute inflation pressures, support a cautious, wait-and-see approach, with room to adjust if adverse risks materialize (Figure 9).

The key point is flexibility: policy does not need to always move pre-emptively, but it should act opportunistically—at the right time, with the right mix of tools.

Authorities can pivot toward monetary easing or targeted fiscal support if trade-related shocks begin to weigh more heavily on growth. Any shift toward a more supportive stance should be carefully sequenced and calibrated to domestic slack and inflation conditions, while preserving exchange-rate flexibility and remaining vigilant to financial stability risks.

Before I conclude, it’s also important to note that, ASEAN+3’s recent experience underscores an important lesson: monetary policy alone is not enough to secure price stability under high uncertainty, especially when inflation reflects a mix of demand pressures and supply-side disruptions.

Over the past few years, as economies faced energy and food price shocks alongside reopening dynamics, many ASEAN+3 authorities employed a well-calibrated mix of tools—monetary tightening to contain demand and anchor expectations, fiscal support to cushion households and firms, and targeted supply-side measures to ease domestic price pressures.

The region’s success in maintaining price stability amid various shocks underscore an important point: price stabilization in today’s environment depends on a tailored policy mix that addresses each economy’s specific inflation drivers and constraints, rather than relying on a single instrument or approach.

Closing Remarks

Let me conclude with a few reflections.

Over the past several years, central banks across ASEAN+3 have shown that they can deliver on their core mandate of maintaining price stability—even under extraordinary stress. Their credibility has been hard‑earned, and it has served our region well.

But success has not come from monetary policy alone. It has come from strong macro‑financial fundamentals, and from the nimble use of a broad toolkit—including macroprudential, fiscal, and foreign‑exchange measures—to cushion the region from waves of global shocks. This combination has been essential, and it will remain essential in the years ahead.

As we look forward, one thing is clear: the world is not becoming less uncertain. The shocks we face—whether global or regional, supply‑driven or demand‑driven—are becoming more complex. And different shocks require different policy responses. Understanding their nature, their persistence, and their channels of transmission is critical for crafting effective policy.

This also means that monetary policy cannot carry the entire burden. Stability in this new environment requires the right mix of tools, deployed in the right sequence, and supported by coherent communication and institutional coordination.

Finally, our region’s deepening integration brings great opportunities, but also shared vulnerabilities. As production networks and financial linkages intensify, so too does the need for strong regional surveillance, timely information‑sharing, and open policy dialogue. These are not optional—they are prerequisites for resilience in a more interconnected future.

1I thank Catharine Kho, Eunmi Park, and Haobin Wang for their help preparing this speech.

2Monetary Policy under High Uncertainty: A Scenario-Based Approach for Thailand”, Selected Issues, Annual Consultation Report Thailand 2025.