Co-author: Professor Datuk Norma Mansor, Director of Social Wellbeing Research Centre (SWRC), Universiti Malaya

A version of this article was published in The Edge, Malaysia on July 1, 2025.

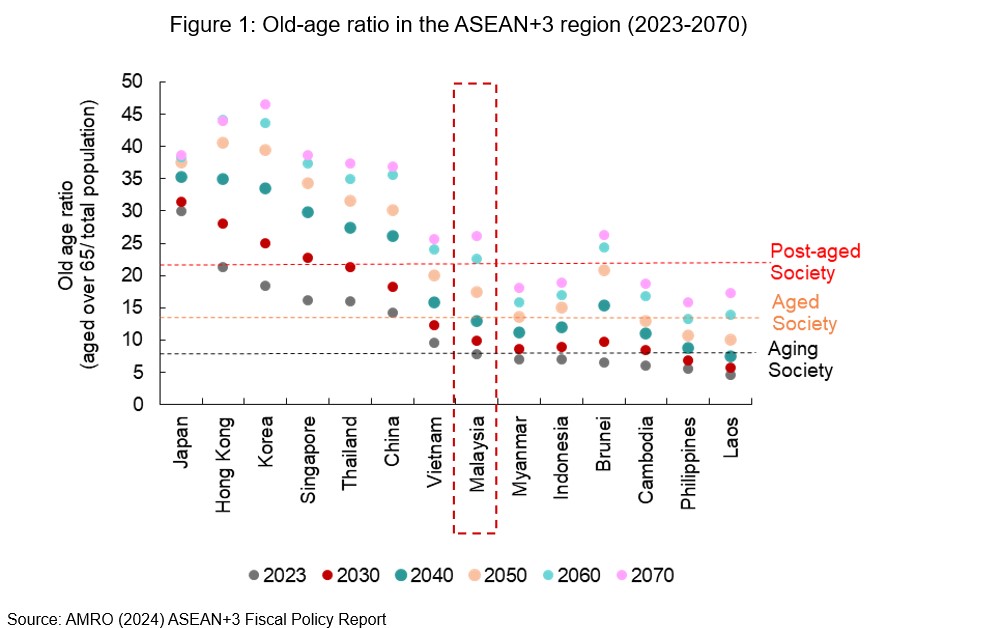

Malaysia became an aging society in 2021, with more than 7 percent of the population aged 65 and above. This demographic shift is accelerating. By 2045, the old-age ratio is expected to double, and by 2060, Malaysia is projected to become a post-aged society, with 14.8 percent or more of the population aged 65 and above (Figure 1).

As life expectancy increases and birth rates decline, the demand for healthcare and social protection is rising. While considerable attention has been given to expanding the coverage and adequacy of the social protection and health systems, far less has been devoted to strengthening the fiscal framework needed to ensure their long-term sustainability.

Fiscal management of social protection and health systems

Managing public spending on social protection and health presents considerable challenges due to several factors.

First, basic income security and access to medical services are widely regarded as fundamental rights. This makes reform efforts politically and socially sensitive, as they often face strong public resistance. Such fiscal rigidity limits the government’s ability to reprioritize spending, especially as aging population exerts increasing and sustained upward pressure on public finance. For instance, Malaysia’s predominantly tax-financed public healthcare system has faced persistent resistance to reform, despite growing concerns about its long-term sustainability.

In addition, rising social protection and health spending can further constrain fiscal flexibility, especially when programs are embedded in legislations. These programs are more difficult to adjust compared to discretionary spending. While this constraint is less pronounced in Malaysia at present – since major tax-financed social protection and health scheme are not legislated – this is could change as the country moves toward institutionalizing these schemes, in line with global best practices. Fiscal rigidity may also increase with the introduction of new initiatives, such as the widely proposed social pension designed to address the countries’ retirement savings gap.

These challenges are not unique to Malaysia. However, the fiscal impacts vary depending on how well the programs are designed, financed, and managed. Given that such expenditures are typically long-term and non-discretionary, robust fiscal planning tools – such as medium-term expenditure frameworks and sustainability assessments – are critical. A sound public financial management (PFM) framework that integrates future health and social protection spending into a forward-looking fiscal strategy is essential to maintaining fiscal discipline while meeting rising fiscal commitments.

Key weaknesses in current system

Our recent study identifies several gaps in Malaysia’s PFM framework that could undermine the long-term fiscal resilience of social protection and health systems.

1. Fiscal planning remains short-term and reactive.

Although the government publishes a Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTFF) as part of the annual budget, it is presented only at an aggregate level, covering total revenues and expenditures over a three-year horizon. The MTFF lacks sector-specific projections and does not include estimates of future spending needs for areas like social protection and healthcare. It also does not account for medium- to long-term resource requirements associated with population aging or other emerging social risks. While more detailed projections may exist internally, the absence of publicly disclosed sectoral information limits the MTFF’s role as a transparent forward-looking planning tool.

2. Institutional responsibilities are not clearly defined.

At present, the Ministry of Finance is responsible for overseeing the fiscal sustainability of social protection and health spending, but it does so without an explicit legal mandate. Similarly, the Malaysian Social Protection Council (MySPC), which plays a coordinating role across ministries on the formulation of social protection policies, lacks statutory authority or legislative basis to assess long-term fiscal impacts. These institutional limitations make it difficult to fully integrate long-term financial considerations into the planning of social programs.

3. Retirement savings are insufficient for many.

Malaysia’s fully funded, defined-contribution Employees Provident Fund (EPF) system has helped contain fiscal risks often associated with pay-as-you-go defined-benefit schemes. However, retirement adequacy remains a key concern. Only 36 percent of active formal EPF members met the basic savings target of RM240,000 by age 55, the minimum level required for a dignified retirement. A sizable portion of the workforce falls short of this threshold, rising the prospect of increased reliance on tax-financed support in the future. Furthermore, the EPF scheme permits multiple pre-retirement withdrawals and full withdrawal at age 55, both of which may contribute to insufficient retirement savings. Addressing these pressures through more strategic policy development would enhance preparedness and resilience.

4. There is no national aging strategy yet.

Malaysia has yet to endorse a comprehensive national aging strategy to guide an integrated, cross-sectoral response to population aging. A coherent framework would provide the foundation for anticipating and managing future fiscal demands of social protection and health systems. Ongoing discussions to develop such a blueprint are encouraging and should incorporate reforms aimed at supporting long-term fiscal sustainability and alignment with social policy goals.

Reform priorities: strengthening fiscal management

To address these challenges, Malaysia should strengthen its PFM framework by systematically integrating social protection and health spending into a medium- and long-term fiscal strategy. This includes

- Enhancing the MTFF to include sector-specific expenditure forecasts linked to demographic trends, actuarial assessments, and evolving policy objectives.

- Aligning the MTFF with broader national development strategies such as the Malaysia Plan, and potentially with a future National Aging Strategy, would reinforce its critical role as a strategic tool for fiscal planning.

- Institutionalizing analytical tools like demographic projections, fiscal sustainability assessment, and cost-benefit analyses to guide decisions on program expansion, design, and reform, such as adjustments to retirement age or contribution rates.

A forward-looking PFM system, anchored on credible costing and strong links between policy goals and fiscal allocations, would allow Malaysia to navigate economic shocks and demographic transitions while maintaining long-term fiscal sustainability.

At the institutional level, expanding MySPC’s role to include fiscal sustainability assessments of social protection and health systems would allow for more coherent and forward-looking planning. Anchoring MySPC in legislation would strengthen cross-ministerial coordination, foster dialogue on fiscal sustainability and enhance accountability.

Finally, developing a coordinated national framework for social protection and health, underpinned by a comprehensive aging strategy, would help align Malaysia’s social protection and health policy objectives with its fiscal realities.

Conclusion

Malaysia is still in the early stages of demographic transition, offering a valuable window of opportunity to put in place the necessary fiscal guardrails for the sustainable development of social protection systems. Proactively integrating aging-related spending into medium- and long-term fiscal planning and enhancing PFM framework will help mitigate future risks. Taking early action will allow Malaysians to age with dignity, supported by an adequate and fiscally sustainable system.