By Wei Sun

Another version of this article was published in the BusinessWorld on March 26, 2019

The Philippine economy has been experiencing a boom in the real estate sector in the last several years which has contributed to the robust growth of the economy. In the past five years, the real estate sector has contributed about 12 percent to the country’s GDP, and taken up more than 18 percent of bank loans. Not surprisingly, the boom has invited many discussions in the media about risk that it pose to the financial system.

The boom in the real estate sector has been fueled largely by foreign investment. Global manufacturers take space in industrial parks, outsourcing services companies occupy office buildings, and expats demand accommodation close to their work places. In Metro Manila, the Business Process Outsourcing industry takes up 42 percent of the office space over the first three quarters of 2018, and the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGO) contribute another 25 percent. Developers sell 20 to 40 percent of their condominium units to foreigners according to anecdotal evidence. In the Manila Bay area, where many of the POGO are headquartered, rentals rose by as much as 62 percent in the first half of 2018.

Real estate developers have good reasons to feel happy about this foreign–investment-fueled demand, but that is not without risk going forward. Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into the country have shown signs of moderating, as their approvals in recent years have slowed down considerably. If this situation continues in the next few years, then it is likely, according to AMRO’s 2018 Annual Consultation Report on the Philippines, that the demand for commercial and residential properties may soften, causing their vacancy rates to rise and prices to fall, ultimately affecting developers’ cash flows and repayment ability.

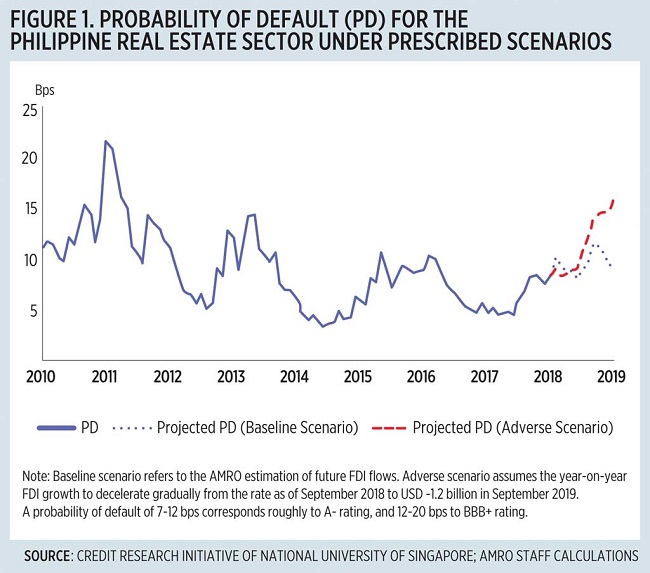

An AMRO model presented in the same report indicates that the 34 publicly-listed real estate companies in the country currently have an average probability of default, or the likelihood of not paying off their debt obligations, equivalent to an S&P A-rating, which implies an adequate repayment ability. However, if FDI flows were to decline sharply to $1.2 billion in September 2019, a magnitude resembling that during the 2008 global financial crisis, the creditworthiness of the real estate companies will deteriorate to BBB+, along with a credit loss of P2.4 billion, enough to wipe out a quarter of the total asset of a median-sized developer.

AMRO estimates suggest that the real estate sector will remain resilient even in an adverse scenario, thanks to their currently benign leverage ratios and liquidity positions. However, spots of vulnerabilities do exist. Developers have been borrowing more aggressively over time, and their financial leverage, or total liabilities as a ratio of net assets, has exceeded 1, or doubled the 2010 level. They have been reducing excess cash on the book, as their short-term assets are more than enough to cover their short-term liabilities, but that has not translated into a higher level of profitability, or a productive use of cash.

Uncertainties surrounding the tax reform, trade tensions, and the POGO industry continue to abound, dampening the longer-term prospect of foreign investment and in turn the real estate sector. The ongoing tax reform may invite scrutiny on the competitiveness of the Philippines as an attractive foreign investment destination. Trade tensions and a global growth slow-down may further weigh on the investment momentum in the country. POGO, relying on overseas demand for online gaming, may be subject to disruption if foreign governments begin regulating the players and facilities or even restricting capital flows into this business. More directly, if the large number of foreign workers in POGO and other sectors are prohibited from working in the Philippines, then the residential property market would lose a significant pool of clients.

These potential risks call for vigilance. Real estate developers should find ways to diversify their sources of revenues, while rationalizing their borrowing from the banking system. Supervisors, aside from regularly monitoring and testing bank exposures to the real estate sector, may want to keep an eye on the risks surrounding the foreign demand and factor them in their models.