After the global financial crisis, economic inequality has been worsening throughout the world. In 2018, it was reported that the world’s richest 1% owns about one half of the world’s wealth, according to The Credit Suisse Research Institute’s Global Wealth Report 2018.

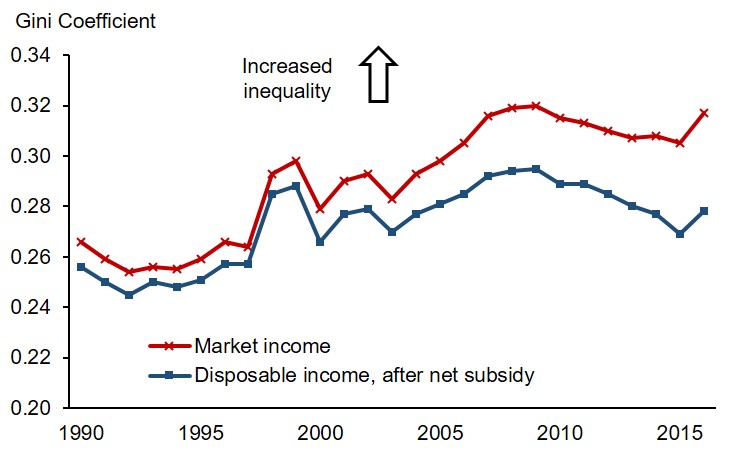

In Korea, concerns about income inequality are also increasing. The country’s Gini coefficient, an index commonly used to measure income distribution among a population, has increased from 0.26 in 1990 to 0.31 in 2015 (Figure 1). As the economy advances, the economic disparity becomes more apparent. According to our 2018 Annual Consultation Report, the national income gap between corporates and households has widened since the early 1990s, reflecting growing national income concentration in firms.

Figure 1. Korea’s Gini Coefficient

Source: Bank of Korea

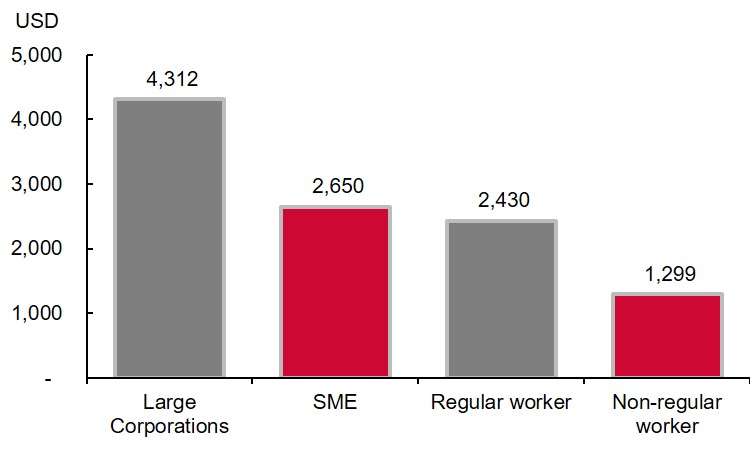

Economic disparity in Korea is caused partly through industrialization led by chaebols – large family-owned business conglomerates – during the 1960s. Although industrialization has transformed the country into a high-income economy, it has widened the gap between chaebols and SMEs in terms of market power, productivity, and wages. In 2017, the average monthly income of those who work in chaebols is about 60% higher than that of workers in SMEs. Employees of chaebols are drawn to better employment terms, leading to a talent gap between chaebols and SMEs. In addition, different employment conditions between regular workers and non-regular workers also contribute to the disparity. Although lower pay and more flexible employment contracts for non-regular workers incentivize companies to hire them, the income and opportunity gap between regular and non-regular workers persists. In 2017, on average, regular workers can earn almost twice as much as non-regular workers do.

Figure 2. Average Monthly Income in 2017

Source: Ministry of Employment and Labor; Korean Statistical Information Service

‘New Economic Policy’ to Tackle Inequality

Since 2017, the Moon Jae-in administration has introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) with the aim of decreasing income and wealth inequality. It seeks to do so through four pillars, namely income-driven growth, job-centered economy, innovative growth, and fair competition.

The rationale behind ‘income-driven growth’ and ‘job-centered economy’ is that a redistribution of income will boost domestic consumption and hence overall growth. The minimum wage was increased by 16.4% in 2018 and 10.9% in 2019. Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and unemployment benefits were implemented. Protection for non-regular workers has also been strengthened while converting a non-regular worker to a regular employee is actively encouraged.

The ‘fair competition’ pillar aims to level the playing field between chaebols and SMEs. Laws and regulations related to the prevention of unfair subcontracting were amended to regulate technology transfer and to ensure fair price setting between these two groups. To improve corporate governance and prevent abuse by chaebol owner families of their dominant shareholding power, the chaebols are encouraged to reduce cross/circular shareholding in the group.

The objective of the ‘innovation-led’ growth pillar is to bolster innovation and start-ups, as a new growth engine of the Korean economy. Regulatory sandbox has been implemented since April 2019 to reduce regulatory barriers to innovation. Public financial institutions provide direct and indirect finance to support startups and venture capitalists. Chaebols are encouraged to share profits gained from an innovative product with their subcontractors.

It may be too early to assess the outcome of the NEP at this juncture, as the policy is intended to address long-term structural issues. Although the labor market weakened after the large increase in the minimum wage, it may not be due to the ineffectiveness of the NEP; economic slowdown as well as structural factors, such as aging, technological advancement, and skills mismatch, also contributed to deteriorating employment conditions. In addition, rebalancing between chaebols and SMEs and structural reforms always takes time.

Further policy consideration

The NEP would be able to tackle economic inequality. However, it can be complemented by other policies.

An increase in the minimum wage is aimed at reducing wage differentials among employed workers, but some studies have found that higher minimum wage could aggravate income inequality among the population due to rising unemployment and increasingly limited job opportunities for the youth and low-skilled workers. With technological advancement, increasing the minimum wage may incentivize employers to replace low-skilled workers with machines to perform routine tasks, which threatens their job security. To mitigate these adverse impacts, raising the minimum wage should be done gradually and along with policies to improve labor productivity and create higher-skilled jobs. As skills upgrading takes time to bear fruit, social welfare policies – particularly unemployment insurance – should be implemented to mitigate the negative short-term impacts of retrenchment and to facilitate the transition of the labor market toward higher-skilled jobs.

Separately, policies to enhance SMEs’ competitiveness should be implemented. SMEs should get more support on R&D as well as human capital and IT development so that they can improve innovation and competitiveness. More collaboration among SMEs, in particular across different industries, can create new products or new services in the new economy. In addition, searching for new clients by tapping into overseas markets could also lessen SMEs’ reliance on chaebols and the domestic market.

Income disparities can give rise to economic and social tensions and affect long-term growth. With the NEP in place, Korea is facing an opportune time to employ the right policies to tackle these fundamental issues to ensure shared prosperity and inclusive growth.